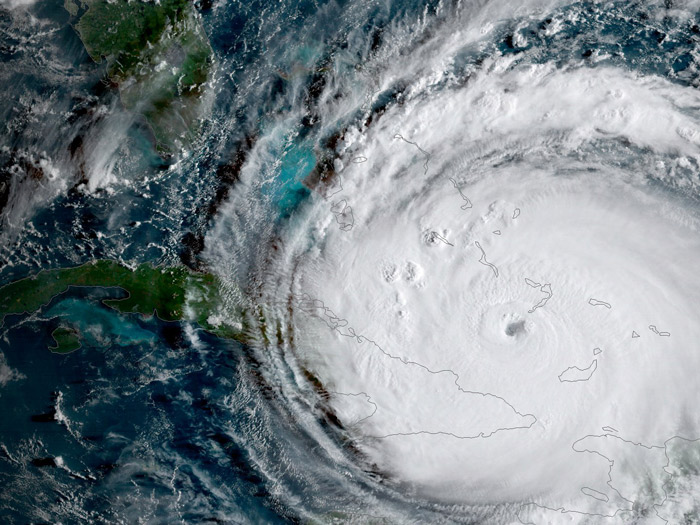

Over the past few weeks, hurricane Harvey plummeted into Texas, and record-breaking hurricane Irma plowed through the Caribbean and into the west coast of Florida—with smaller hurricanes Jose and Katia.

Technically, a hurricane is a tropical cyclone. According to NASA, the name “hurricane” is regional, applying only to tropical cyclones that form over the Atlantic Ocean or Eastern Pacific ocean.

“Earlier in the week, Irma sustained 185 mph winds for more than 24 hours, a record length of time for a hurricane in the Atlantic.” Vox reports. “Irma was a Category 5 storm for around 3 days—which is also nearly a record.”

Hurricanes form in equatorial regions where the ocean is heated by the sun, providing energy for the storm; warm air rises from the ocean’s surface to form thunderstorms. Then, upper-level and surface winds blow these clouds into a circular motion, forming a “tropical depression”—a tropical cyclone with wind speeds below 62 kilometres per hour. Once winds inside the storm reach 119 k.p.h., the storm officially becomes a hurricane.

With hurricanes Irma, Jose, and Katia all brewing simultaneously, the storms have attracted global media coverage. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicted this year would bring many hurricanes.

Two large-scale patterns dictate whether or not a given year will host hurricane-inducing conditions: The El Niño/La Niña cycle and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO).

During an El Niño, ocean temperatures tend to be warmer than usual, creating strong winds that usually prevent hurricane formation. The AMO also fluctuates between cool and warm seasons; the former phase is more suitable for hurricanes than the latter. The AMO changes every few decades, and the warm phase has been in play since 1995.

The NOAA notes that this year’s El Niño is “weak or non-existent,” which explains why these three back-to-back hurricanes were likely to occur. Coupled with a suite of other conditions, this hurricane season did not come as a shock to atmospheric scientists and weather specialists.

Furthermore, extensive discussion about the role of climate change on the intensity of these hurricanes has clouded the scientific community.

In a recent article, The Scientific American outlines how climate change has both clear and debatable impacts on these storms. For example, rising global temperatures triggered glacier melt and has lead to a rise in sea levels.

“The seemingly modest 1 foot of sea level rise off the New York City and New Jersey coast made a Sandy-like storm surge of 14 feet far more likely, and led to 25 additional square miles of flooding and several billion extra dollars of damage,” The Scientific American reports, based off the paper “Increased threat of tropical cyclones and coastal flooding to New York City during the anthropogenic era.”

A study published in Nature also emphasizes that hurricanes are getting stronger due to climate change. The most damaging storms ever recorded have all occurred within the past two years. In addition to warmer sea surface temperatures overall—which increases moisture level in the atmosphere and the flooding power of recent hurricanes—raised temperatures result in higher winds, with “roughly eight [metres] per second increase in wind speed per degree Celsius of warming.”

However, climate change cannot be shown to be the direct cause of these storms. The Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory maintains that it is premature to connect human activities or greenhouse gases in the atmosphere directly to hurricane strength and scope. Although climate change is not directly responsible for the hurricane count, it is augmenting the damage they cause.