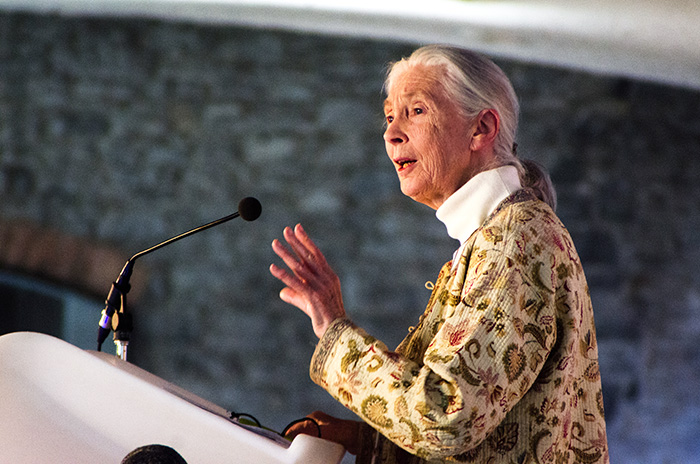

At the Young Women’s Veterinary Association International Conference on Sustainable Veterinary Practice on Oct. 6, the animal calls were so life-like there could have been a chimpanzee in the room.

“This is me, this is Jane, in chimpanzee language,” primatologist Dr. Jane Goodall said.

Goodall, founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and UN Messenger of Peace, is considered to be the world’s foremost expert on chimpanzees. Awarded England’s highest honour, Dame of the British Empire, in 2004, Goodall has been the recipient of many prestigious awards over the years for her work on humanitarian and animal rights issues.

“I was born loving animals,” Goodall said. “[As a child] I determined I would grow up, move to Africa, live with wild animals, and write books about them. And everyone laughed at me [.…] The war was raging in Europe, we had very little money […] and I was just a girl, and girls didn’t do that sort of thing.”

In 1960, under the mentorship of famed paleontologist and anthropologist Dr. Louis Leakey, Goodall began her groundbreaking research on the behaviour of the chimpanzees at the Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve in Tanzania.

“Nobody else had ever done anything like that [before],” Goodall said.

Goodall’s observations of the chimpanzees fishing termites out of mounds using sticks and other tools were revolutionary in that it forced a redefinition of the way scientists view animals.

“It was believed that there was a sharp line dividing us humans from the rest of the animal kingdom,” Goodall said. “Today, we know we are part of that animal kingdom, not separated from it.”

Goodall’s close analysis of the emotional relationship between offspring and their mothers, nurturing behaviour in both genders and territorial war between neighbouring chimp populations showed her the similarities between chimpanzee and human nature.

“Chimpanzees have their dark side […] and their loving side, too,” Goodall said.

Goodall eventually attended Cambridge University for her PhD, which she received in 1965. She was dismayed, however, to discover that the academic world rejected the idea of animal sentience.

“They told me that I had done everything all wrong,” Goodall said. “I shouldn’t have given the chimpanzees names—they should have had numbers.”

It wasn’t until a conference on the study of chimpanzees in 1986 that Goodall was fully exposed to habitat deterioration and inhumane treatment of chimpanzees as a species across the world.

“Chimpanzees were dropping in numbers as a result of the bushmeat trade, commercial hunting, snaring, and the live animal trade,” Goodall said. “I went to that conference as a scientist […] and left as an activist.”

Goodall brought up a few topics relevant to her work as an environmental and animal activist. She described the horrible conditions of industrial farming in wealthy nations paired with the effects of a growing demand for meat.

“About 18 per cent of the greenhouse gases […] responsible for global warming and climate change come from intensive farming,” Goodall explained. “Forests are cut down to house the animals, huge amounts of fossil fuel are used to get the grain to the animals, and the meat to the table, and, of course, a huge amount of water is used to change vegetable protein to animal protein.”

Widespread cow farming and their feces add to the production of methane, which is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

Despite the barrage of modern challenges, Goodall has hope—hope that by better understanding animals, better solutions will be made.

“Animals are indeed sentient,” Goodall said. “Together we can find ways of changing some of these unfortunate cruelties that go on in the world around us.”