The year 2100 has frequently served as a benchmark for climate health projections. Yet, more than half a century has passed since 2100 was first used as a horizon, and the year is no longer a marker of an abstract and dystopian future, but rather a time that will be reached by some alive today.

Christopher Lyon, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill, joined scientists from the University of Leeds as a visiting researcher to help create a new experimental model for a climate warming curve continuing beyond 2100 and into the year 2500.

“We keep saying 2100, and don’t look past 2100,” Lyon said in an interview with The McGill Tribune. “Someone might be forgiven for assuming that whatever is going to happen by 2100 is the stopping point for climate change, but it keeps going after that.”

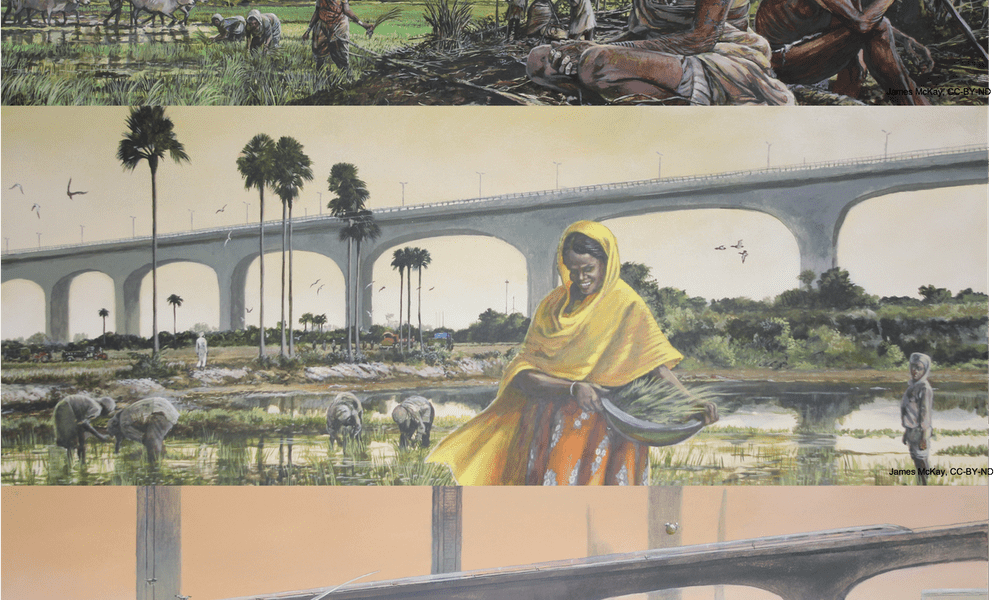

One of the greatest impacts that climate change may have past 2100 is the substantial warming of the equatorial regions around the globe, which would render places such as the Midwest or the Indian subcontinent too hot for human habitation. Humans could be forced to migrate to the poles and scientists would have to develop new artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in farming to adapt crop production to these high temperatures.

“If, and it’s a big if, we don’t manage to meet our climate objectives, and the world does get that much hotter, we may have to reprioritize our aims,” Lyon said. “It could be that we end up in a kind of triage politics where we have to think about sustaining [human] life, rather than some of the places and ecosystems we hold valuable now.”

The crux of climate change negotiations of the future could lie between allocating resources toward either conservation or adaptation. For instance, extensive irrigation and water conservation systems designed to be controlled remotely could benefit areas such as the North American plains, where water could become scarce. There is also a very real possibility that personal protective equipment will be needed to safely venture outside in equatorial regions.

“If we delay, […] it gets much harder to do,” Lyon said. “The planet will be warmer, there will be more CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and we will need a much greater level of technological intervention to stop emissions.”

While Lyon’s research is mostly aimed at modelling the climate crisis further into the future, his team nevertheless takes time to highlight the challenges climate change poses to current governments.

“Maybe we need to think about how we structure our institutions for the kind of decision-making that needs to happen to mitigate climate change,” Lyon said. “[This system is] responsible for producing the emissions […] but it’s also the system we’re trying to solve [climate change] with.”

While a complete restructuring of our political systems might seem daunting, or too large a task to be completed before the Earth warms by two degrees Celsius, Lyon remains optimistic about humanity’s prospects for overcoming these obstacles.

“We are kind of missing an opportunity right now to do something collectively as a species to address a challenge facing us that could provide a lot of meaning to people’s lives,” Lyon said. “The generations that meet this challenge can tell their grandkids about [it] when [they] might ask ‘What did you do in the climate crisis when it was really bad?’”