“The test was simple,” former McGill MBA student Mohammed Ashour wrote in an email to The McGill Tribune. “Would you be willing to drop out of school to pursue this idea, even if you lost the Hult Prize?”

In 2013, Ashour and his classmates Gabe Mott, Shobhita Soor, Jesse Pearlstein, and Zev Thompson came together to compete in the prestigious international Hult Prize in social entrepreneurship. The team would go on to launch Aspire Food Group, with a mission of providing alternate forms of sustainable protein.

“I wanted to form a team where each individual brings a unique point of view and set of skills,” Ashour said. “Not just demographic and cultural diversity, which are critical, but also diversity in thought, experience, and worldview.”

The Hult Prize challenged the teams to the daunting task of tackling food security and poverty, particularly in urban slums. Around that time, Ashour ran into friend and Montreal physician Dr. Mohamed Slim.

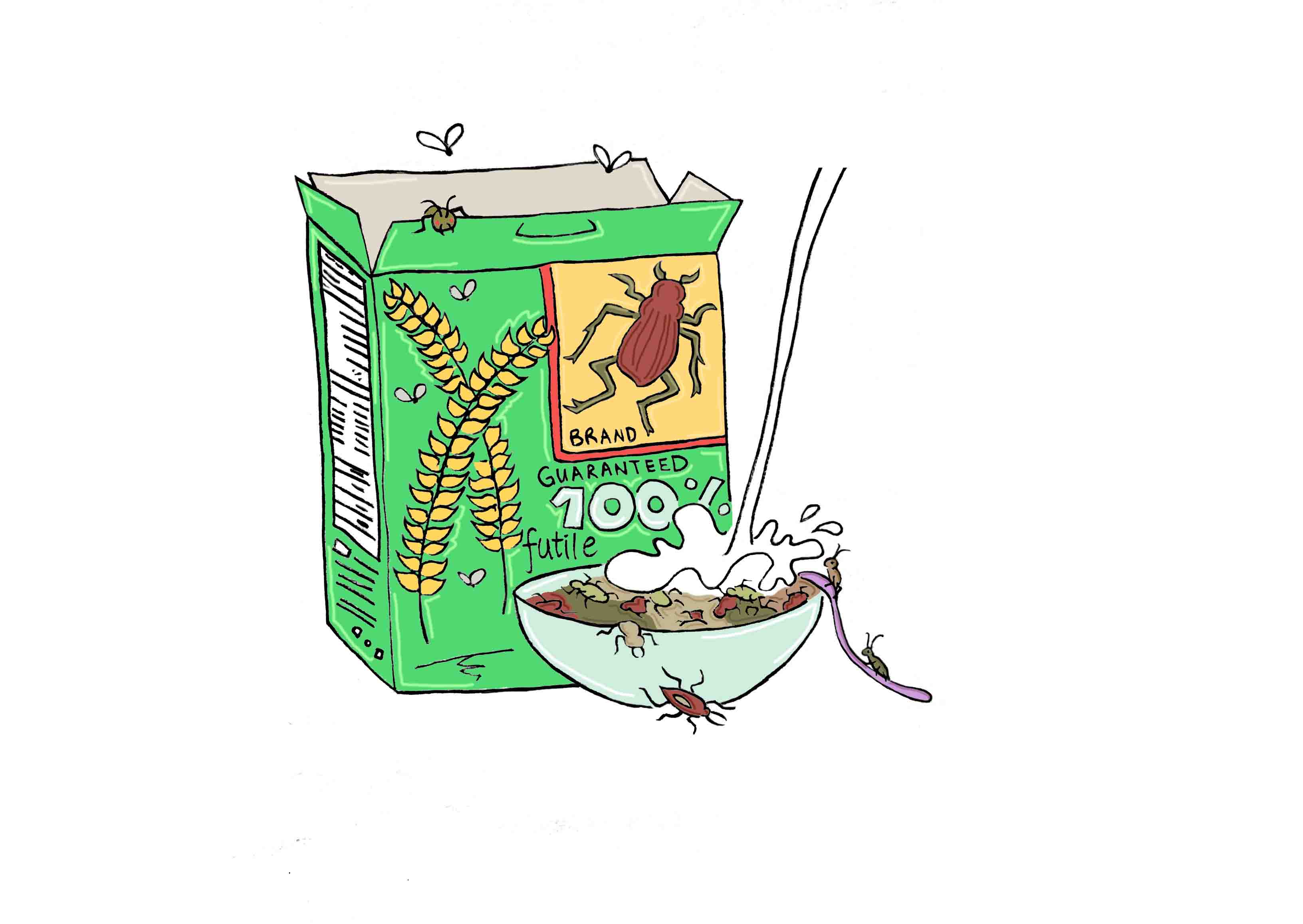

“I struck up the topic about food security and poverty and he narrated a story about insects as food,” Ashour said. “That was the spark.”

Protein is a vital macronutrient, but, animal protein is often extremely expensive and resource intensive. With these limitations, protein deficiency is common worldwide. Dr. Slim recommended the team to seek out a creative alternative.

“People love bugs,” Dr. Slim said. “If you deal with something really common, people will say ‘ah, clever, but I’m not interested.’ If you tell them something disgusting but plausible, you win.”

And their idea did just that. In March 2013, the team beat Harvard University to progress through the Hult Prize Regional Finals and then went on to win in September of the same year.

Using the $1 million seed capital prize, Aspire Food Group was born.

Ashour advocates for learning entrepreneurial lessons outside the classroom. However, if students haven’t found their “ah-ha!” idea just yet, Ashour suggests searching for start-ups they’re interested in and asking for work.

“I guarantee that the ‘tuition value’ of learning on someone else’s dime will be one of the most invaluable experiences you will have,” Ashour said. “If I’m being blunt, it may be more valuable than anything you will learn in the classroom.”

Despite the win, there were still hurdles for the team.

“The biggest obstacle was validation,” Ashour said. “We had this extremely optimistic concept of getting people in Thailand, Kenya, or Ghana to put a basket full of noisy crickets in their already crowded dwelling!”

After many long nights and trips back to the drawing board, Aspire now utilizes sensor technology and the internet-of-things to generate live data on the insects throughout their lifespans.

Not only is Aspire fulfilling the original Hult Prize challenge of spearheading urban food poverty, it has branched into normalizing insect consumption in Western countries.

“While food insecurity is less problematic in Canada and the United States, than, say, Kenya, food sustainability has become a major problem,” Ashour said.

Less than two years after establishing their first U.S. pilot cricket farm, Aspire launched the site aketta.com: An online information and recipe hub and retailer for all things crickets.

“It is estimated that 80 per cent of water resources in the U.S. are consumed by livestock production” Ashour said. “Insects are objectively an outstanding source of nutrition […] with the added advantage of being incredibly environmentally efficient.”

The now 30-person company doesn’t seem to be slowing down anytime soon.

“We are currently making significant investments into biological and technology research and development” Ashour said. “Our goal is to develop modular farms that can be deployed in any country around the world.”

For the aspiring entrepreneurs out there, Ashour advocates starting now.

“If you have an idea you are obsessed with […] don’t fear failure,” he said.