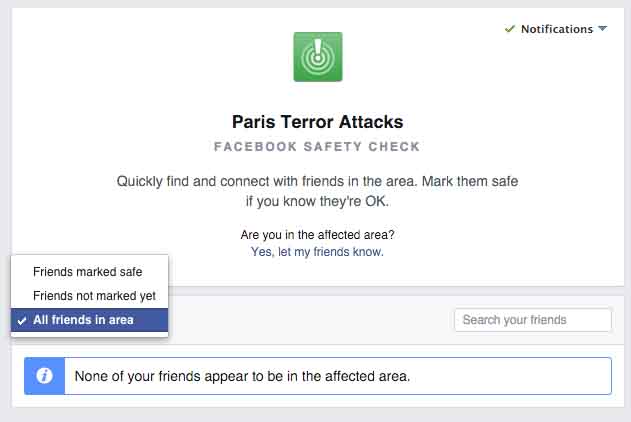

On Nov. 12, 2015, 43 civilians lost their lives in twin bombings claimed by ISIS in Beirut. The next day, 129 civilians lost their lives in multiple ISIS attacks in Paris. Both tragedies have drawn in sympathy and well-wishes from around the world, but this support has been met with controversy. Many are upset that the events in Paris garnered more support and attention from Western countries than the events in Beirut. For example, Facebook gave users the ability to add the French flag to their profile picture as a sign of solidarity with France, but presented no such option for Lebanon.

Writers from USAToday, The Huffington Post, and The New York Times have claimed that this imbalanced reaction stems from Westerners holding lives of other Westerners above those of Middle Easterners, and consequently, the loss of their people of lesser importance. Researchers explain, however, that the difference in reactions to these two massacres is largely based on relatability. Witnessing a close family member suffering is undoubtedly bound to cause more grief and pain than watching a distant acquaintance experience the same thing. This experience—called empathy—is the ability to understand another person’s condition from their perspective.

“It is perhaps one of the most defining features of humanity,” wrote Farriss Samarrai in an article for UVAToday.

This past January, a group of researchers from McGill’s Pain Genetics Lab set out to prove how the relationships between two individuals could affect emotions. To do this, the team first treated McGill undergraduate students with a painful stimuli and asked them to rate the pain. The students rated the pain similarly when tested alone or with a stranger; however, when tested with a friend, the pain levels felt by the student had increased. This increase in pain, the researched hypothesized, was due to a greater amount of empathy felt between the individuals, causing them to feel each other’s pain.

Taking their research a step forward, the scientists pharmacologically inhibited glucocorticoid receptors—involved in stress—in their participants. When they did this, they observed higher pain ratings. By blocking the receptors, the individual felt a lower level of social stress, and thus a higher vulnerability to pain. In essence, the person was less worried about being in an unfamiliar environment with an unfamiliar person, and consequently, had more capacity to feel their pain. When the tests were emulated in mice, the team observed similar results.

The group’s efforts provided valuable insight about how an individual is able to empathize. The inner biological actions of empathy, however, have continued to remain elusive. To shed more light on this, researchers from the University of Virginia looked at how individuals respond to threats. The team took fMRI brain scans of individuals in an experimental condition where either they, their friend, or a stranger was placed under the threat of electric shock. When the threat was to the self or a friend, similar areas of the brain, specifically the anterior insula, putamen and supramarginal gyrus, were activated. However, when the threat was to a stranger, these areas showed little activity.

“Familiarity involves the inclusion of the other into the self, that from the perspective of the brain, our friends and loved ones are indeed part of who we are,” the researchers explained in their paper.

Through close familiarity, one person’s pain is felt by others. This is precisely the reason why there was an immense outpouring of support for those affected by the tragedies that occurred in Paris and Beirut. But this is also partly the reason why more support and recognition were shown towards Paris by Westerners. France is more ‘familiar’ to Western countries because it shares some of the same cultural and historical backgrounds as other western countries. This causes Westerners to associate with the people in Paris more than those in Beirut, and thus, feel their pain more.