Professor Anthony Ricciardi’s team thought they were going to be studying the Asian Clam—an invasive species—when they dropped their sediment-collecting grabs below the surface of the St. Lawrence River last year. Instead, they found the microbead—a type of microplastic defined as any debris less than five millimetres in size.

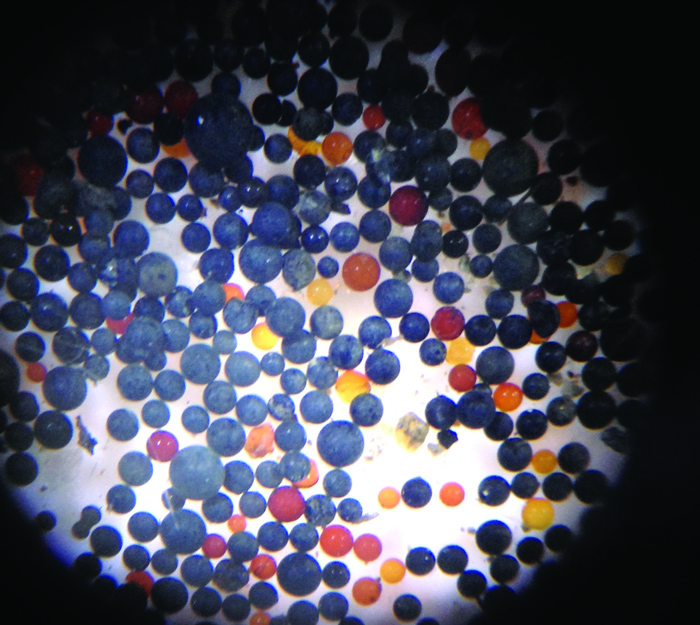

Rowshyra Castañeda, the lead researcher and a former master’s student now pursuing a degree at the University of Toronto, kept noticing small, multi-coloured beads present in almost all of the sediment. When prodded, the beads, would shatter, indicating their synthetic nature. Further tests proved the hypothesis correct; the beads were in fact made of polyethylene, the most commonly used plastic.

“These could be particles of synthetic plastics formed by fragmentation of larger plastics,” Ricciardi said. “But most of these are probably manufactured on purpose, as small granules for industrial abrasives.”

Industrial abrasives are used in cosmetics and household products to slough off dirt and skin. Unfortunately, the granules used in the products are non-biodegradable. They have started to accumulate in aquatic systems because wastewater treatment plants can not filter them. This is a result of not only their size, but also their buoyancy. It is also the reason scientists didn’t think to look for microplastics in lakes or rivers; researchers assumed they would float out into the oceans.

Scientists believed freshwater systems would wash the beads out into the ocean, and therefore focused their attention there. Unfortunately, Ricciardi and his team are discovering otherwise.

After the team’s initial observations, Ricciardi sent his students out to collect more samples—this time focusing on the microbeads. What they found was startling.

Samples taken from a total of 10 sites along a 320-kilometre freshwater section of the river showed microbeads present at eight of the sites. According to Ricciardi, some sites had as many as 1,000 beads per litre of sediment.

“This rivals that of what has been found in oceans,” he said. “We believe we underestimated the concentrations [of these microbeads.] We show that they’re accumulating and that they’re ubiquitous [in water sources.]”

The microbeads develop a film when introduced to nature. This allows them to settle and accumulate at the bottoms of lakes and rivers.

The long-term effects this might have on the food system are still unknown.

However, a study done at the University of California showed the immediate dangers of microbead consumption for aquatic animals.

Consumption of unaltered, lab-made microbeads induced slight stress on the livers of tested fish, yet the fish exhibited severe liver failure when fed microbeads collected from nature. The polyethylene in the microbeads had absorbed pollutants from the water; consequently, the toxicity of the beads had risen to a million times more than that of the surrounding water.

Ricciardi believes that the microplastics have a negative impact on aquatic environments.

“We have reason to believe there will be a cost [on the environment,]” Ricciardi said. “We have reports that the plastic has been found in fish—hundreds of them.”

Previous reports have speculated about the presence of microbeads in fish, but the team plans to take the next real step in finding out. With funding from the Quebec Centre for Biodiversity Science (QCBS), Ricciardi and his team have started collecting round gobbies, a species of bottom-dwelling fish. Their goal is to examine the stomachs of these fish to see how prevalent these pollutants are in the food web, and how many of the microbeads are being consumed.

Other species will have to be tested and the ecotoxicity measured to determine the severity of the costs that microplastics will have on any environment.

Several states in the U.S. have already passed legislation banning microbeads from products. Canada has yet to propose such regulations. Ricciardi believes that microplastics should be regulated everywhere.

“I think they can be phased out,” he said. “This is an emerging issue in marine ecology, but companies can definitely use natural products as abrasives—[…] something that will break down.”