McGill’s Department of Global and Public Health hosted a seminar on Oct. 18 with Dr. Brian Ward, former director of the J.D. MacLean Centre for Tropical Diseases and professor in McGill’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. Dr. Ward gave an eye-opening talk titled “Micronutrients and microbes: Some things we know and many things we don’t.”

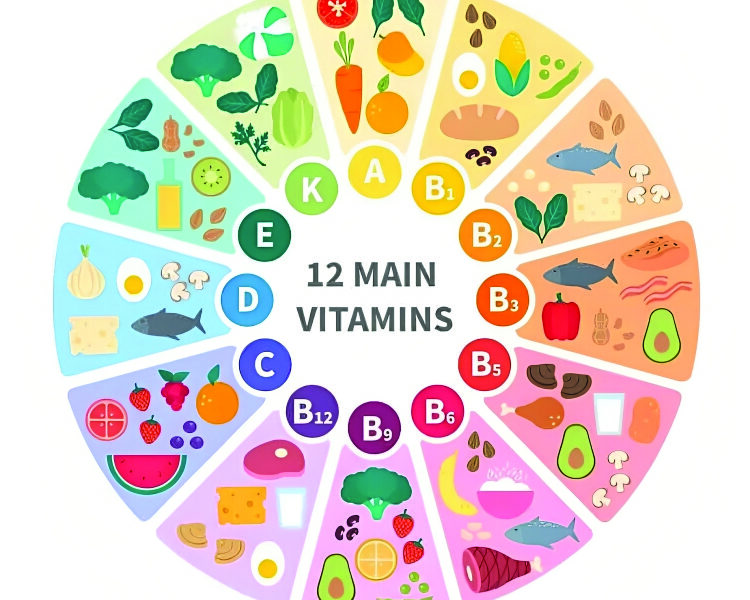

Micronutrients often refer to vitamins—including vitamins A through E and K—or minerals such as iron, zinc, and iodine. Although humans need them in very small amounts, they are critical to overall health and disease prevention in the body.

Diet is the primary source of most micronutrients, but other sources include sunlight, which enables the production of vitamin D in our skin.

“The gut microbiome contributes significantly to our access of several micronutrients, particularly the B vitamins, via the metabolism of the bacteria,” Dr. Ward explained.

Because micronutrients play essential roles in various bodily processes, including immune and bone functions, micronutrient deficiencies can lead to health problems.

For example, Joseph Bramhall Ellison established the association between vitamin A deficiency and measles. “In 1937, [he] found that if you give cod liver oil, a dietary supplement that is extraordinarily high in vitamin A, to babies, you could reduce mortality from measles by 80 per cent,” Dr. Ward noted.

50 years later, scientists repeated this experiment in South Africa and demonstrated a 50-per-cent reduction in mortality rate for children with severe measles.

Unfortunately, micronutrient deficiencies can pose notable dangers for people in certain occupations that necessitate strong visual acuity at night.

“Our eyes contain rods responsible for vision at low light levels. These rods are particularly sensitive to low vitamin A levels, so one of the first signs of vitamin A deficiency is night blindness,” Dr. Ward explained. “This is why pilots in World War I and later have been routinely tested for vitamin A deficiency.”

Dr. Ward also highlighted that a surplus of micronutrients can be just as dangerous as a deficit.

“If you don’t have enough iron, you’ll have anemia and neurodegeneration. If you have too much iron, you’ll have arthritis, liver disease, and overwhelming infections,” Dr. Ward noted. “Similarly, if you don’t have enough zinc, you’ll have mental lethargy. If you have too much zinc, you’ll have nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and an increased risk of prostate cancer.”

Having established the critical role that micronutrients play in our health, Dr. Ward gave an overview of the history of nutritional science, concluding by looking ahead to his hopes for the future of the discipline.

From around 1850 to 1960, the field was just beginning to come into its own. “In this era, research scientists were discovering new micronutrients and figuring out how to prevent individual nutritional deficiencies,” Dr. Ward said.

Between 1960 to 1990, public health messaging emphasized the qualities of individual nutrients, but in the present era—1990 onward—the focus has shifted to overall dietary patterns. More positive messaging around diet, such as the Mediterranean diet—a primarily plant-based diet featuring the consumption of whole grains, olive oil, fruits, vegetables, beans, and nuts—has emerged.

Over the next two decades, Dr. Ward anticipates that the gut microbiome will become a focus in the world of nutritional science.

“The gut microbiome has vital impacts on the activities of the brain, heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, bone, muscle, skin, kidneys, and bladder, but very little is known about the micronutrients supplied through the gut microbiome,” he said.

Dr. Ward ignited the audience’s thinking by posing a few crucial questions to guide future research on human health.

“How does the gut microbiome react to micronutrients? Do micronutrients interact with other micronutrients? If you have the wrong gut microbiome, does it reduce the absorption of micronutrients?” he asked.

In his closing remarks, Dr. Ward pointed to the need for more research to investigate how micronutrients act alone, in concert with one another, and in concert with the gut microbiome.