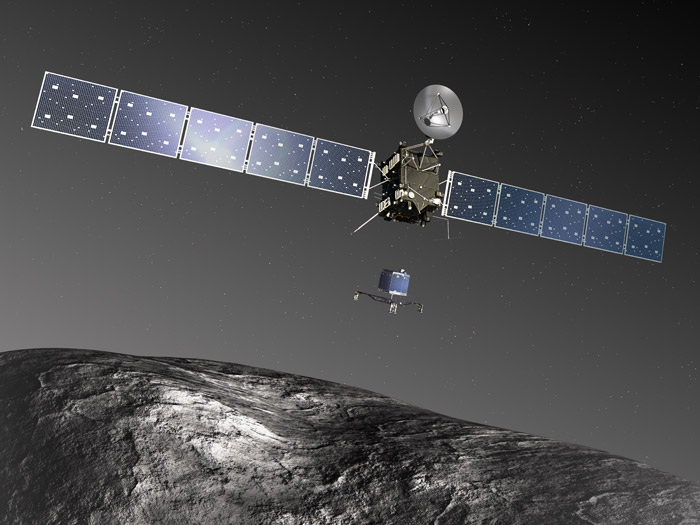

At 16:03 GMT on Nov. 12, 2014, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta mission’s Philae lander touched down on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Its arrival marked the end of a decade-long journey that spanned 6.4 billion kilometres, and the first successful landing of a spacecraft on a comet.

The Rosetta mission, named after the Rosetta Stone, is expected to explain some of the mysteries shrouding the birth of our solar system by taking an unprecedentedly close look at a comet.

Comets offer a wealth of information about what our planetary neighbourhood looked like billions of years ago. Unlike planets, where chemical reactions alter their composition over time, comets have remained relatively unchanged for billions of years.

Scientists believe that the data Philae collects will reveal the age, chemical composition, and history of comets in our solar system. Additionally, this data could indicate how much of Earth’s water came from collisions with comets, and even what effect comets had on the development of life.

“Rosetta is trying to answer the very big questions about the history of our Solar System,” explained Matt Taylor, a Rosetta project scientist, in an ESA press release. “What were the conditions like at its infancy, and how did it evolve? What role did comets play in this evolution? How do comets work?”

The probe has already provided scientists with some insight into the makeup of the comet—even before its landing. An instrument called ROSINA (Rosetta orbiter sensor for ion and neutral analysis) analyzed the compounds present in the comet’s coma—a halo of evaporated gases that are released when the comet orbits near the sun.

Most of the data that scientists are eagerly awaiting, however, will be produced by the Philae lander on the comet’s surface. A variety of detectors will measure the mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties of the surface of the comet.

Descending and touching down on the comet was a rocky affair. A comet is a relatively small object, so there is very little gravitational force to prevent an incoming object, like a probe, from bouncing and flying off into space. Philae’s landing harpoons—which were designed to hold the probe to the comet’s surface—failed, and after an initial impact, the craft bounced off of the rocky landscape and travelled at 38 cm/s for almost two hours until it landed about a kilometre from its initial landing site.

Philae then bounced a second time, although it landed again within seven minutes. Its final landing spot was much shadier than the one intended—bad news for the lander’s solar powered batteries.

Though the lander was able to start collecting data, limited power supply meant that its operational time frame was significantly shorter than scientists had anticipated. Philae’s battery died soon after sending the last of its data back to Earth, although scientists hope that it may be revived when the comet’s orbit brings it closer to the sun.

Despite these setbacks, the general outlook on the comet landing is a positive one. The results produced by Philae will have an immense impact on what we know about not just the contents of our solar system, but how it came to exist as we know it.

“It’s been an extremely long and hard journey to reach today’s once-in-a-lifetime event, but it was absolutely worthwhile,” said Fred Jansen, ESA Rosetta mission manager. “We look forward to the continued success of the great scientific endeavour that is the Rosetta mission as it promises to revolutionize our understanding of comets.”