NASA has always been an institute of great scientific accomplishment and innovation, but this comes with a hefty price tag. As the agency moves forward in its three-stage plan to put humans on Mars, the public agency’s budget is under heavy scrutiny. Increased pressure has been put on NASA to develop more cost-effective alternatives.

In its Fiscal Year (FY) 2017 budget estimates, NASA requested $19 billion USD from the U.S. government, projected to increase to $20.4 billion USD by 2021. With such a large budget, it seems natural to assume that the 2020 Mars rover will be superior to its predecessors in every way. In 2017, $377 million USD will go to the 2020 Mars rover exploration mission alone, according the FY 2017 budget estimates.

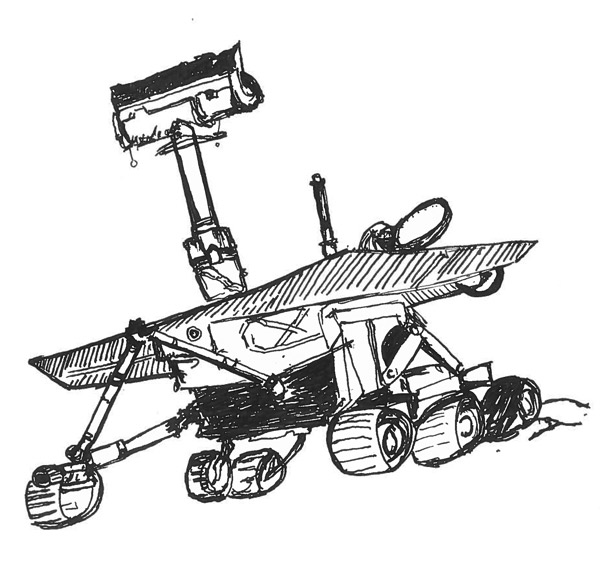

The 2020 rover will be heavily based upon the Curiosity rover, which launched in November 2011. While the Curiosity rover has been hailed as a huge success, NASA stated that a major reason for re-implementing much of the 2011 technology in the 2020 rover is to cut costs. Considering the net cost of the 2020 rover, the fact that NASA had to reuse technology, and that the agency is largely funded by taxpayers, it is obvious why people may look for more cost-efficient solutions to space research.

In recent years, NASA has started to put significant effort into deploying nanosatellites, such as cube satellites, in order to maximize research while cutting costs. Nanosatellites have a mass between one to ten kilograms and provide a smaller, less expensive alternative to conventional satellites. One such example is the CubeSat Launch Initiative. Cube satellites are a specific type of nanosatellite measured in standard 10x10x11cm units, called U’s. Started in 2008, this initiative organizes partnerships between NASA and educational institutions all over the US to launch cube satellites into space. The consistent size of cube satellites makes it easy to standardize the launch process, allowing NASA to launch 49 CubeSats into space since the beginning of the 2008 initiative.

In Fall 2016, U3 electrical engineering student Paul Albert-LeBrun founded a space club called The McGill Space Systems Group. Albert-Lebrun said his interest in space exploration has been a part of his life since he was a child, citing his father’s job in the aerospace industry as the original source of inspiration.

“We have pretty much visited everything [on Earth…],” Albert-Lebrun said. “Space is something we don’t know much of and there are so many things to explore about it.”

This interest in the unknown drove Albert-Lebrun to seek out aerospace internships, resulting in work placements at several different companies, including aerospace giant Lockheed Martin.

The McGill Space Systems Group is part of the wave of university groups, such as those taking part in NASA’s CubeSat program, working with nanosatellites. The group is currently designing and building a nanosatellite to identify gravitational waves and other space activity. Albert-Lebrun hopes that through this process he can make the concept of space exploration and technologies more accessible to students and overall more useful and interesting.

“The idea of nanosatellites is very important […],” Albert-Lebrun said. “You can build in a week, they are more affordable, and are built on a smaller scale [….] This is the only way that the space industry can survive. There is still the financial limitation but we have to move towards a more agile system.”

Under NASA’s budget restrictions, nanosatellites are looking to be more and more promising. The next generation of space explorers can join in the effort now to provide a more sustainable future for the space industry.