In the past 20 years, hundreds of new cities have sprung up around the world. Some are new political centres, others are aspiring trade hubs or green cities. But, whether it’s Astana, Putrajaya, or King Abdullah Economic City, the reason is the same: To increase economic growth. Surprisingly, though, many of these new cities are overlooking the risk of rising sea levels when building on coastlines.

Sarah Moser, assistant professor in the Geography department, spotted these trends while working on a forthcoming study of new cities. Along with collaborator Idowu Ajibade of Portland State University, she is studying the motivations behind founding new cities and their vulnerability to natural disasters.

Building new cities on coastlines is often justified as a way to relieve urban overcrowdedness, particularly in the Global South. However, as Moser found, the companies building these new cities are not really concerned about social ills such as overpopulation—their goal is profit.

“It seems logical, right?” Moser said. “Let’s make new cities to address crowding and congestion and so people can live in a humane, clean, green environment. But, then, when it really comes down to it, new cities are often a way of justifying massive real estate developments.”

The continuing desire for luxurious waterfront real estate prompts the building of cities for profit on the water, regardless of climate change related costs. Forest City, which a Chinese company is building on artificial islands in Malaysia, is expected to hold 700,000 people. But, because the project is driven by real estate, investors aim to buy 70 per cent of the houses purely for investment purposes and the price will only inflate as they try to sell to the highest-bidding interested homeowner. This case is illustrative of similar problems in many other new cities.

“Can the person earning two dollars a day taking plastic water bottles to a recycling centre ever hope to buy a condo worth two hundred thousand dollars?” Moser said. “No. Such projects are for elites, although they are supposed to be for the growing middle class. Real estate in new cities is often bought not by the poor or middle class who need homes, but by the super rich who already own multiple homes.”

According to Moser, some projects are also using eminent domain laws—laws which allow the government to take private land for public use—to seize the area that they plan to build on. The vacated residents sell their land to the government for cheap only for the new developments to be unaffordable.

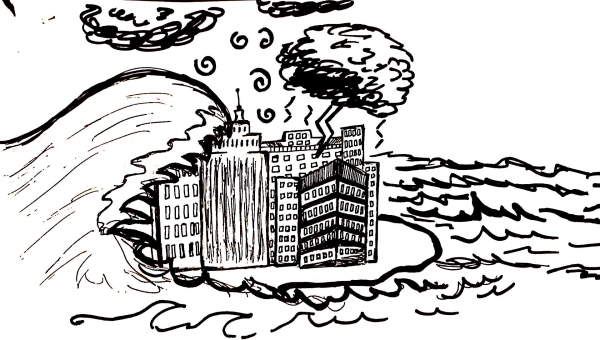

Of the 120 new city projects Moser is examining, she estimates that between 35 and 38 per cent of them are located on the coasts, making them vulnerable to climate change as sea levels rise and storms become stronger. Worryingly, only eight of 120 city projects even mentioned climate change.

Even worse, these new cities inflict ecological consequences themselves. Coastal areas are very sensitive to environmental changes. In the case of Forest City, sand is sucked off the seafloor and redistributed in piles to create islands. In the process, a delicate ecosystem of coral reefs, fish, and an intricate food web that humans rely on is damaged. Unfortunately, many environmental laws regulating these developments are weak or poorly-enforced.

While it might seem to make more sense to fix existing infrastructure in places like Lagos or Jakarta, building an entirely new city is easier from a political perspective. There is no existing population to question decision-making; there is no need to play politics or take bribes. And the profits are enormous: A technology company like Cisco, for example, can make about 400 billion dollars from a new city.

Moser isn’t against new development and feels strongly that Canadians shouldn’t be telling other countries what’s best for them. However, if new development is necessary, local people should be consulted. Perhaps, with more consultation, companies and governments would be building more sustainable and less vulnerable cities further inland rather than on beaches.