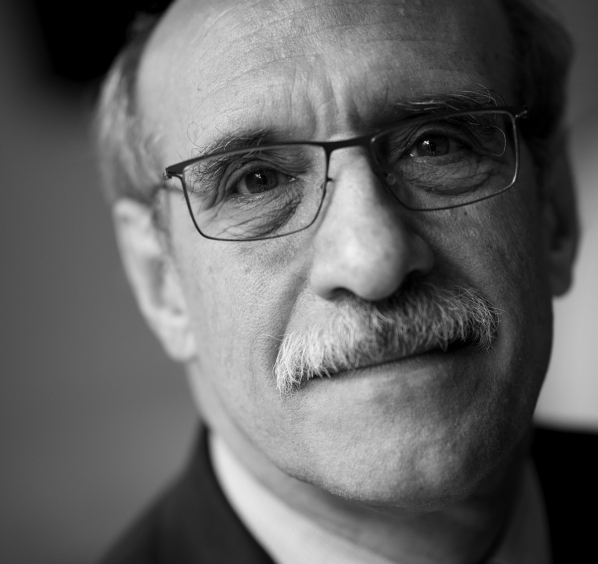

On Sept. 26, a sea of undergraduate and graduate students packed into the Pollack Hall auditorium. They were there to listen to Martin Chalfie, an acclaimed geneticist and winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, speak about his discovery of the green fluorescent protein (GFP).

GFP is a bioluminescent tracker derived from the crystal jelly, a species of jellyfish that glows bright green under UV light when activated by calcium ions in seawater. By attaching GFP to a protein, scientists can observe its pathway through the systems of living organisms. Chalfie found the protein particularly interesting because his research primarily concerned nematodes, a type of roundworm with transparent skin, which makes it easy for him to observe GFPs flow. The biological marker allowed scientists to move away from dead specimens and instead work with live ones, since GFP doesn’t hurt or damage the organism.

“[Before], in order to do any of [our] experiments, we had to prepare the specimen, which meant killing it,” Chalfie said. “We were just getting a step of what was going on; we had no idea of what was happening over time.”

GFP has a vast range of applications that go beyond its original intent. From detecting the HIV-1 virus to locating explosive dynamite in active landmines, the versatility of bioluminescence is impressive.

Chalfie’s talk was not limited to the conclusions of his experiments. He also shared some valuable wisdom with the audience on the true nature of science. According to Chalfie, there are certain traits that society has attributed to scientific success that are blatantly untrue.

For one, few scientists are actually lone geniuses. This stereotype likely emerged from prodigious pioneers of the past, such as Galileo Galilei or Albert Einstein. Today, however, scientific research is done by teams of devoted individuals, whose passion and hard work negate any need for a photographic memory. Chalfie used his university transcript as an example of this.

“I showed my transcript at a college reunion after [winning] the Nobel,” Chalfie said. “Everyone came up to me and said, afterwards, ‘Thank you for showing that. I was embarrassed about my transcript.’”

Chalfie also proposed an amendment to the scientific method based on his experience. The scientific method is a structured manner of conducting an experiment that has long been drilled into the heads of eager baking-soda-and-vinegar science fair students. The six steps begin with a question and end with a discovery. In the modern and professional context of research, Chalfie said, the discovery tends to come before the hypothesis. It is not uncommon for raw data to emerge in an unexpected way that will require scientists to completely rethink their approach. According to Chalfie, science is chock-full of stumbling and failure, and falls short of the exceptionally precise reputation that precedes it. As a result, a great deal of discoveries actually happen by accident.

“I know people who have had very successful experiments by throwing their parts on the floor,” Chalfie said. “It’s not exactly the scientific method, but it’s something!”

In fact, the cultivation of the bioluminescence from jellyfish was one such accident. Osamu Shimomura, an organic chemist and marine biologist who shared the 2008 Nobel Prize with Chalfie, noticed that certain elements in seawater activated the glow in the organism because he threw his species into the sink one night before closing the lab.

Although Chalfie paints a generous picture that attempts to distribute much of the credit of his Nobel Prize to chance and luck, it is clear that his contribution to science lies not only in his team’s discoveries, but also in his unique scientific approach.