The Cystic Fibrosis Translational Research Centre at McGill University and the University of British Columbia are looking in unexpected places for potential cures—under the sea. Dr. David Thomas, Chair of McGill’s department of biochemistry and Canada Research chair in molecular genetics, focuses his research on investigating quality control of proteins.

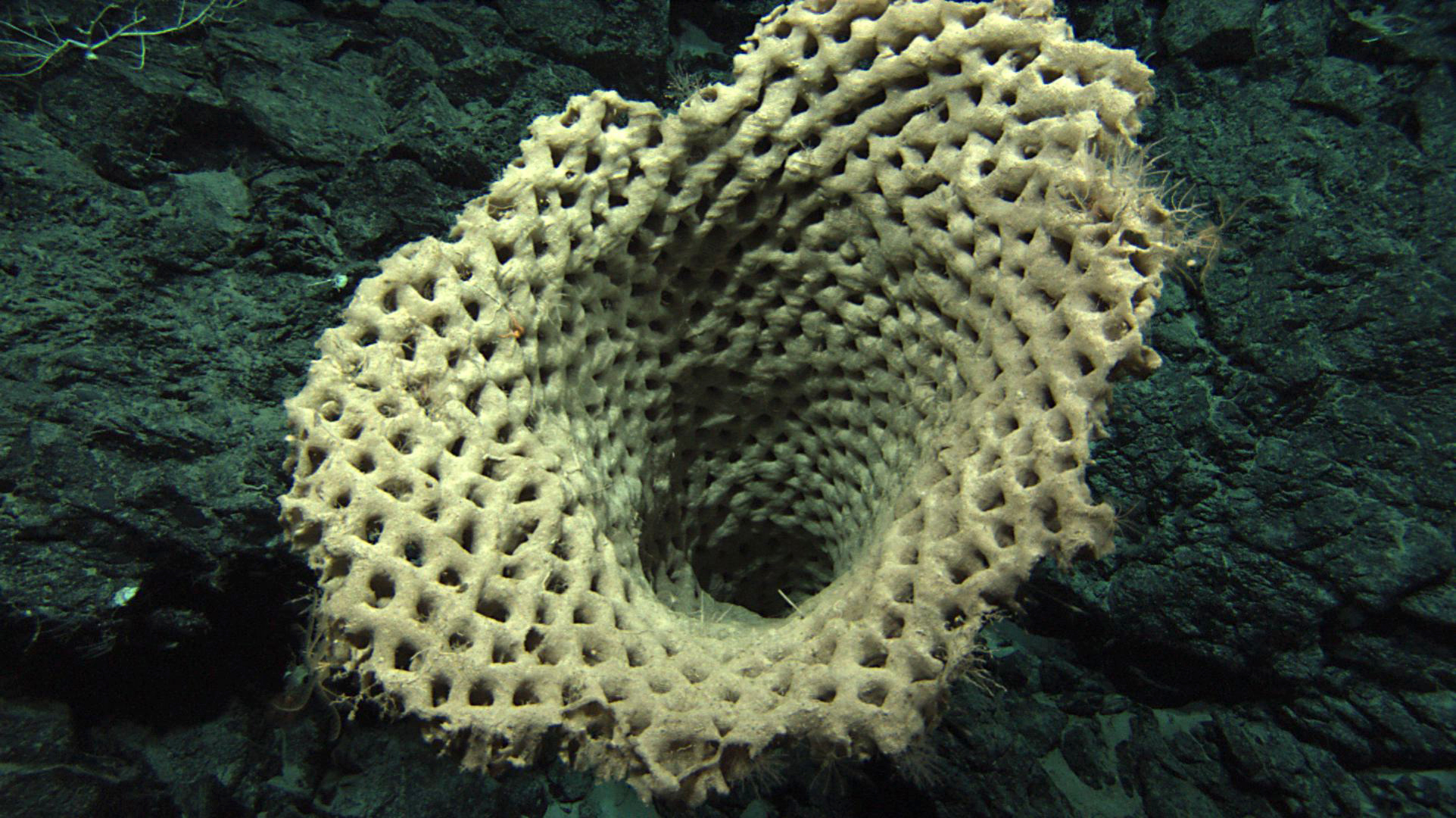

The researchers have discovered a chemical that restores the function of the defective protein that causes cystic fibrosis. It comes from an unusual source: marine sponges from the South Pacific.

Proteins are the ‘workhorses’ of molecular life—both by functioning as the main structural building block and taking part in almost every cell activity. If a protein is not functioning properly, it can cause disorders: namely protein trafficking diseases like cystic fibrosis. Since these abnormal proteins are harmful, the body has developed mechanisms to eliminate them. Dr. Thomas’ lab investigates these mechanisms, hoping to find treatments for disorders like cystic fibrosis.

“We work on determining … the rules of protein quality control,” Dr. Thomas explained. “If you’ve ever driven an AMC car, and you drive a BMW, you know what quality control is.”

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that is caused by a mutation in the gene of a protein called CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator). This protein is necessary for moving chloride and sodium ions across membranes in the lungs. In CF, the protein is mutated, so that ion transport cannot function properly, and viscous secretions build up in the lungs.

About five years ago, Dr. Thomas began to research treatments for the defective protein that causes CF. In collaboration with Professor Raymond Andersen, a natural products chemist who specializes in isolating novel molecules from marine sponges, he looked into a variety of chemicals that could correct the basic defect that causes most CF cases.

It turned out that one marine sponge provided a chemical extract that corrects the localization and function of CFTR. They purified this compound and traced down one important chemical—lantonduine. Despite this success, Dr. Thomas’ team will continue investigating other compounds that might play a role in treating CF.

Looking to the future, Dr. Thomas does not believe developing treatment will be easy.

“The problem with cystic fibrosis is that it is a rare disease … about 90,000 people have it worldwide, and big companies are not going to be interested in working on orphan [or rare] diseases”.

This problem is not unique to CF.

“Between six to eight per cent of the population suffer from an orphan or rare disease, but there is such a vast array of them, that no one is going to develop a therapy when you only have 200 people [in need]”.

Still, studies like those conducted by Dr. Thomas’ team could be potentially applicable to a wider range of patients.

“Something that works for cystic fibrosis [could] also work for other protein trafficking diseases,” Thomas said.

“The market is 90,000 [patients, but perhaps] they can add to it by looking at other protein trafficking diseases.”