Approximately 70 000 people worldwide live with cystic fibrosis (CF). Around 80 to 95 per cent of them fail to recover from lung infections, which can lead to rapid lung function decline and even death. Disturbingly, the standard treatment for lung infections fails in around one third of patients.

In a recent paper, Dao Nguyen, an associate professor of Medicine at McGill, and a team of scientists from across Canada and the US discovered that treatment could fail in CF patients because of P. aeruginosa aggregation, which increases antibiotic resistance in bacteria.

CF is a life-threatening genetic disease that affects various organs, such as the lungs, pancreas, and intestines, in children and young adults. This condition is caused by the impaired function of a protein—the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator— that controls the flow of water and salt in and out of the body’s cells. This helps to regulate the production of mucus, a slippery substance that lubricates and protects airway linings.

When the function of this protein is impaired, the mucus becomes abnormally thick and sticky. This thick mucus can block the airways, leading to coughing, breathing problems, and an increased risk of lung infections.

A major cause of lung infections in people with CF is a bacterial species called Pseudomonas aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa thrives in moist environments and can easily colonize the lungs of people with CF, creating chronic infections that are extremely difficult to treat.

Early antibiotic eradication treatment (AET) has been the standard treatment to wipe off P. aeruginosa in children with CF; however, it sometimes fails. Although previous studies have investigated the reasons for which AET failed, they were performed in laboratory settings, so the variables dictating the failures were controlled and known.

“The human airway is a complex physical and chemical environment, with specific nutrients, a specific oxygen concentration, and a vast array of molecules and cells that can influence the way bacteria grow and behave,” Nguyen wrote in an email to The Tribune. “As such, it is very difficult to reproduce all the conditions in the lab.”

In the new study published in Nature, Nguyen and her team examined the association between P. aeruginosa and failure of AET, aiming to validate whether previous results based on laboratory specimens still hold true in real-world patients. The study found that children who weren’t able to clear P. aeruginosa using AET had increased anti-Psl antibody levels.

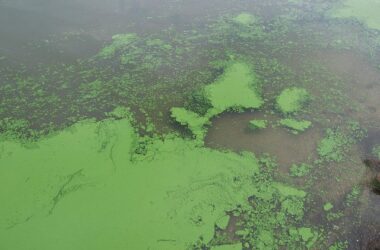

“A high anti-Psl level would suggest that there is a high concentration of P. aeruginosa biovolume in the sputum, [which is the thick mucus produced by the lungs when the lungs are diseased or damaged.]” Amanda Morris, the lead author and a research associate at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, said in an interview with The Tribune.

“While there are many different reasons why antibiotic eradication treatment may fail in children with cystic fibrosis, we found that the sputum from children who failed to eradicate P. aeruginosa had more Psl, as well as larger and more bacterial aggregation.”

The researchers used a method called the microbial identification passive clarity technique to visualize bacterial interactions in the patient’s sputum.

“This technique is suitable for this study because it allows us to clear sputum without disrupting or disturbing the P. aeruginosa structure, so we can see bacterial colonization in exactly what the patient has coughed up,” Morris said.

Overall, this study proposed that the aggregation of P. aeruginosa is a primary contributor to AET failures among people living with CF. Not only have the findings added to the existing literature on lung infections in CF patients, but they have also laid a path for future clinical strategies to improve the effectiveness of AET.

“The findings could help identify who is at risk of failing eradication therapy and thus require more aggressive treatment,” Nguyen wrote. “They could also help identify a new therapeutic approach to improve eradication.”