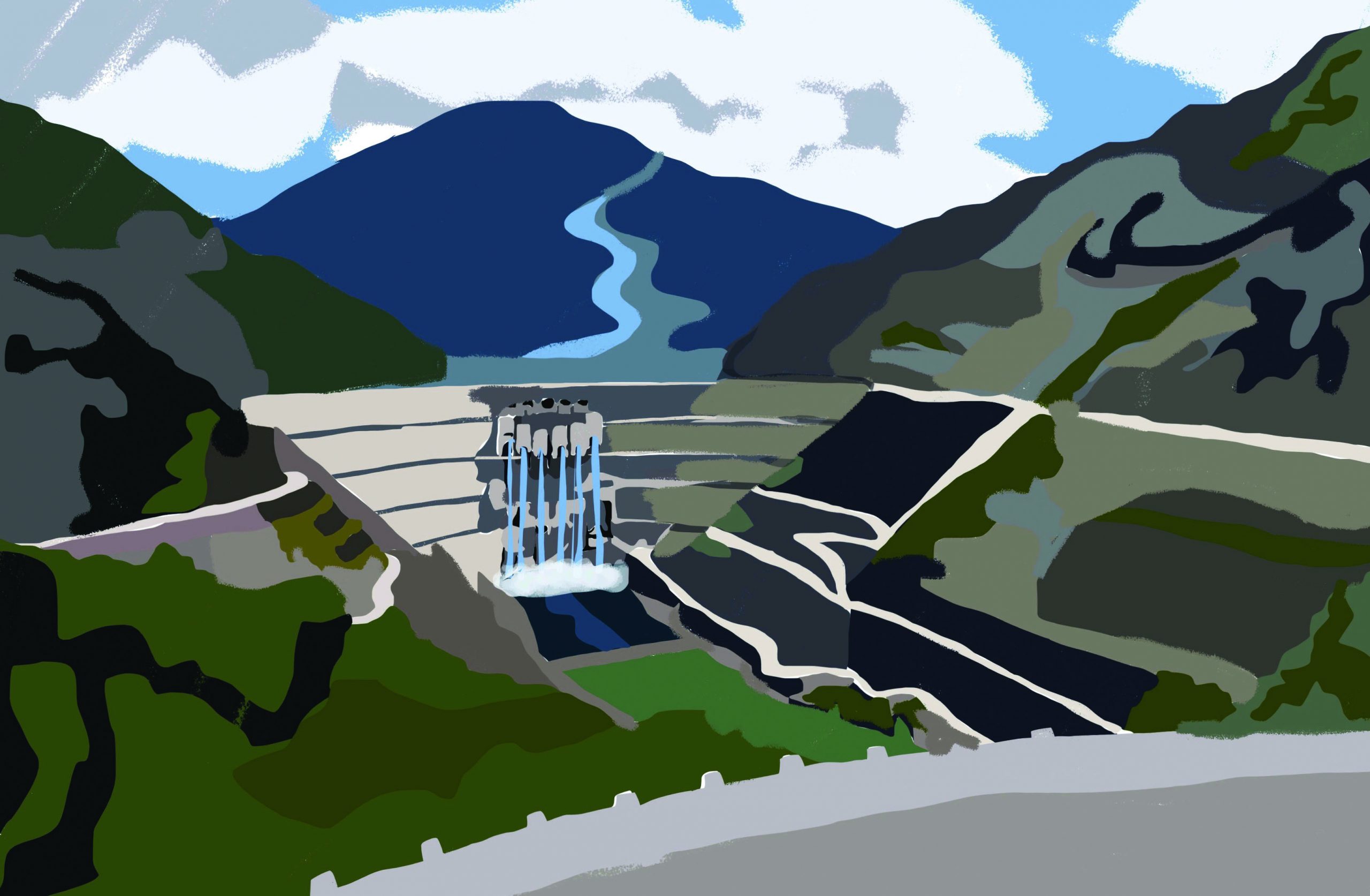

Many hydropower dam projects have been proposed around the world as countries shift toward renewable energy sources, in line with United Nations’ (UN) 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. However, a recent study conducted by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) found that these proposed dam projects threaten the free-flowing status of 260,000 kilometres of major rivers around the world, such as the Amazon, Congo, and Irrawaddy.

Free-flowing rivers are characterized as those whose flow and connectivity are unaffected by human-induced changes. A study conducted in 2019 found that two-thirds of major rivers have lost their connectivity to dams, resulting in devastating consequences on aquatic ecosystems.

“[Dams] create a barrier in the river that, in most cases, cannot be surpassed by organisms that naturally would want to traverse the river system,” Bernhard Lehner, associate professor in McGill’s Department of Geography and member of McGill’s Global Hydrolab, wrote in an email to The McGill Tribune. “[The dams also] change the natural cycle of high and low water flows downstream of the dam, which can disconnect ecologically vital floodplains from the main river channel. They even can change the water quality as they often release water that is colder and contains less oxygen than natural flows.”

The new study, inspired by the effects dams have on river connectivity, assesses how 3700 hydropower dams currently proposed or under construction will affect the environment. One of the major obstacles of the study, however, was obtaining data regarding the projects.

“There is no international group or organization that collects and freely distributes information on global dams,” Lehner wrote. “We only had one database available to us, which was compiled by a research colleague and which only included planned hydropower dams. So we are missing many other dams in our study, such as irrigation dams or dams built for flood protection. To overcome this general problem, we have now founded our own international consortium called Global Dam Watch.”

The study also found that the energy produced by these dams would contribute to only two per cent of the renewable energy needed by 2050 to keep the global temperature increase below 1.5 degrees Celsius—a small benefit with a hefty ecological price tag.

With the World Hydropower Congress taking place in September and the upcoming UN climate and biodiversity summits, the researchers hope that policy-makers will take their findings into consideration and make informed decisions that benefit everyone—instead of sacrificing ecosystems for the sake of clean energy.

Lehner clarified that such a debate does not call for an end to all hydropower projects: The study includes a comprehensive list of science-based solutions to build hydropower dams in a more sustainable way, such as using computer simulations to find less intrusive dam locations.

“The best solution […] is likely the most simple one, avoid building new hydro dams that are not essential, [like] those that produce little energy but have large environmental consequences,” Lehner wrote. “In the past, we have often built hydro dams, or other types of dams, on an opportunistic basis [….] We have not always asked whether this particular dam is indeed the most useful to be built.”

The team believes that research similar to theirs influenced the European Commission to set a goal of removing barriers from 25,000 kilometres of rivers as part of their “Biodiversity strategy for 2030.”

“We can now, quite easily, produce tools that help energy planners to prioritize ‘better’ from ‘worse’ future scenarios of dam locations,” Lehner wrote. “The ultimate decisions remain to be made by politicians and managers, but science can support them in this task in order to arrive at informed decisions, which we believe is an important step forward.”