Digital Rights Management (DRM) technology has permeated our phones, our computers, even our coffee makers. In theory, DRM is meant to protect content creators from piracy; however, its critics are quick to disagree. According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, DRM technologies “impede innovation, security, and basic user rights and expectations, while failing to inhibit copyright infringement.”

Although DRM is not at the front of most people’s minds when they read a book on an e-reader or listen to music on an iPhone, it plays a major role in how media is consumed and what sources it can be accessed from. DRM ensures that eBooks bought from Amazon can only be read on a Kindle, and Microsoft can limit the number of computers that can run a single licence of Office.

While it’s possible to get around DRM and, for example, read books from the Kindle store on a Nook, the expertise and time required to do so provides enough of a barrier that the average consumer is forced to either own two different devices, or purchase content from only a single provider. The pervasiveness of DRM turns it into something to be assumed rather than questioned.

Occasionally, DRM does win the spotlight. When Microsoft initially unveiled the Xbox One, gamers were outraged because of the “always-online” functionality that prevented players from borrowing games from friends or purchasing second-hand editions. The reaction of the Xbox community was so overwhelmingly negative that Microsoft ended up scrapping the concept.

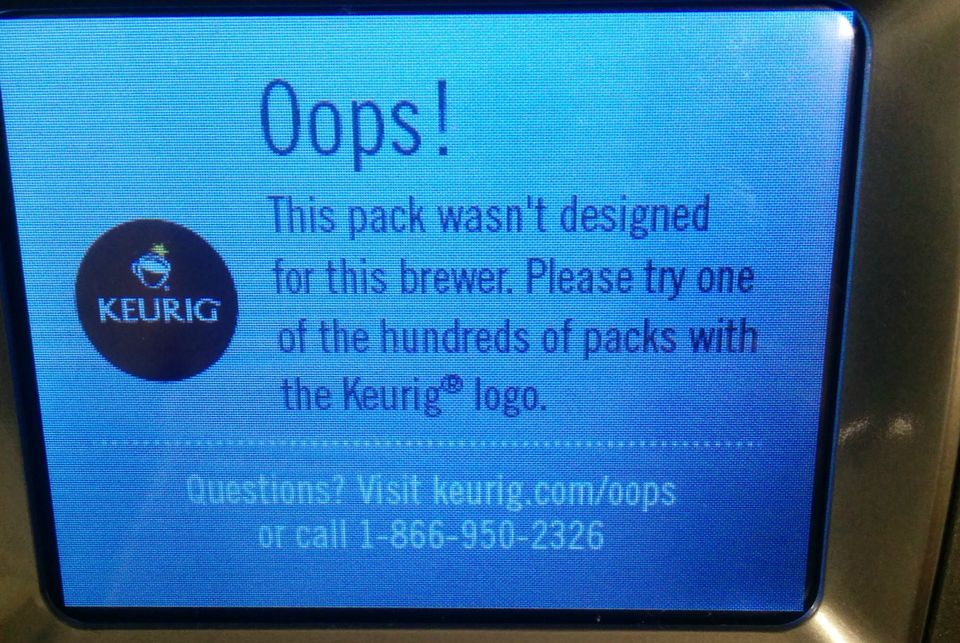

Ignoring consumer opposition to DRM can land a company in hot water, as Keurig has recently discovered. The coffee machine giant released its ‘Keurig 2.0’ in 2014, quietly adding a feature that prevented new machines from reading K-cups that it hadn’t produced. Despite consumer backlash, Keurig has stood by its decision to add DRM to the coffee industry. It saw a 12 per cent decline in revenue in Canada in the financial quarter following the Keurig 2.0 release.

DRM opposition can be seen as being moral. Opponents think that the practice goes against individual rights and gives too much power to large corporations. On a more practical level, DRM can also lead to major security vulnerabilities. In the early 2000s, Sony used software called XCP to restrict customer use of the music on CDs produced by the company. It was later revealed that this software left users’ computers vulnerable to third-party attacks.

DRM is also criticized for its inefficacy. In theory, the technology is intended to prevent piracy. In practice, it is still possible for users to circumvent these restrictions. In fact, many methods of doing so can be found with a quick Google search; typing “Keurig 2.0” into the search engine prompts “keurig 2.0 hack” as one of the first suggestions. Jailbroken iPhones, an array of file conversion software, and programs that rip movies off of DVDs are all examples of how easy it is to get around DRM.

For most, DRM is little more than an inconvenience, like traffic jams. Its ubiquity causes it to fall off of the radar, except for the occasional media frenzy. This becomes a problem when the inconvenience turns into a liability, as was the case with Sony in 2005. Without an informed consumer base, it’s easy for DRM to be used in such a way that consumer rights are compromised. This leads to DRM’s greatest danger: It’s everywhere, but no one realizes.