Sea turtles “lost years” uncovered

When sea turtles hatch, the first few hours of their lives unfold as a desperate obstacle course as they attempt to reach the ocean. Dodging sea gulls, footprints, and crabs, many of these scampering hatchlings—little over an inch in diameter—do not survive the trek from their nest to the water. For the baby sea turtles that do withstand this test of survival, little is known as to what happens to them until they become juvenile turtles—the size of a dish plate—which return to the coastal areas where they forage and continue to mature.

For decades, scientists have tried to discover the whereabouts of these sea turtles during their oceanic stage, also termed their “lost years,” before they return to the coast. This task proved difficult, as researchers lacked an effective method of tracking the creatures—satellite tags proved too bulky and impeded the organisms’ movement.

However, as technology improved, the tags got smaller. This enabled marine scientist and sea turtle biologist Kate Mansfield and her lab at Florida International University to properly track the turtles and map out their “lost years.”

The team remotely tracked young loggerhead sea turtles in the Atlantic Ocean using solar-powered satellite transmitters the size of smartphones. They collected 17 hatchlings from the beaches and raised them until they were three and a half to nine months old. At this point, the turtles’ shells were up to seven inches long—large enough for the transmitters to be glued on for tracking. Mansfield and colleagues then released the turtles from a boat 11 miles offshore in the Gulf Stream off of Florida.

Based on long-term hypotheses, the team expected that the turtles would head up towards the Azores. Surprisingly, findings showed that many of the turtles dropped out of the outer currents leading to the Azores and into the center of the North Atlantic Gyre and Sargasso Sea.

Interestingly, the tags’ temperature sensors were consistently several degrees higher than the turtle’s local water temperature. Sargassum seaweed accumulates in the centre of the gyre, and researchers believe that this temperature difference indicates that the seaweed mats keep the cold-blooded turtles warm, thereby helping their growth.

Mansfield’s team is currently trying to expand their techniques to study other types of sea turtles, hopefully providing us with an even clearer picture of the “lost years.”

Giant virus revived from ancient permafrost

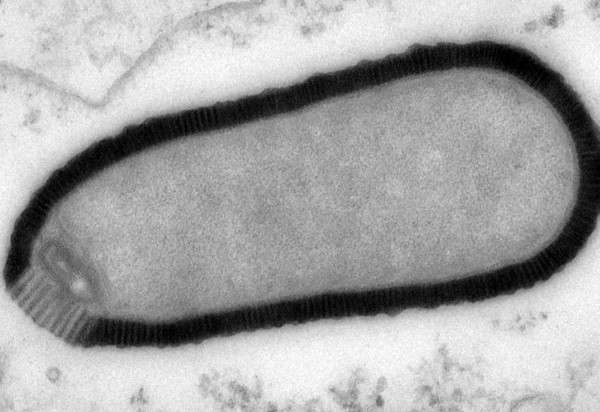

Scientists in France have discovered a new type of virus within a 30,000-year-old sample of thawing Siberian permafrost, and have managed to revive it.

The virus, called Pithovirus sibericium, infects amoebas and is not a threat to humans yet, according to Chantal Abergel, a research scientist at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) and co-discoverer of the virus.

The Pithovirus, named for its large size, is only the third member of the family of giant viruses discovered by virologists a decade ago. Abergel told the Globe and Mail that this specific strain does not mutate frequently, so there is little risk of “genomic drift” into a more lethal strain.

However, researchers still express concern about the discovery.

“The thawing of permafrost either from global warming or industrial exploitation of circumpolar regions [may cause] future threats to human or animal health,” the researchers said in their recent paper published in the National Academy of Sciences.

Permafrost is a good storehouse for microorganisms due to its composition. According to Natural Resources Canada, permafrost is soil at or below the freezing point of water (0 °C) for two or more years, and is usually found underneath the “active layer” of soil. Most of the world’s permafrost is located in high latitudes near the North and South poles. The soil’s cold temperature can be compared to a big freezer that preserves these microorganisms.

While the risk of thawing viruses to human health is still being investigated, the overall message is clear.

“What we’re trying to say is to be careful when you go into layers that haven’t been disturbed in several thousand, or even millions of years. We risk digging up things we don’t necessarily want to see,” Abergel told the Globe and Mail.