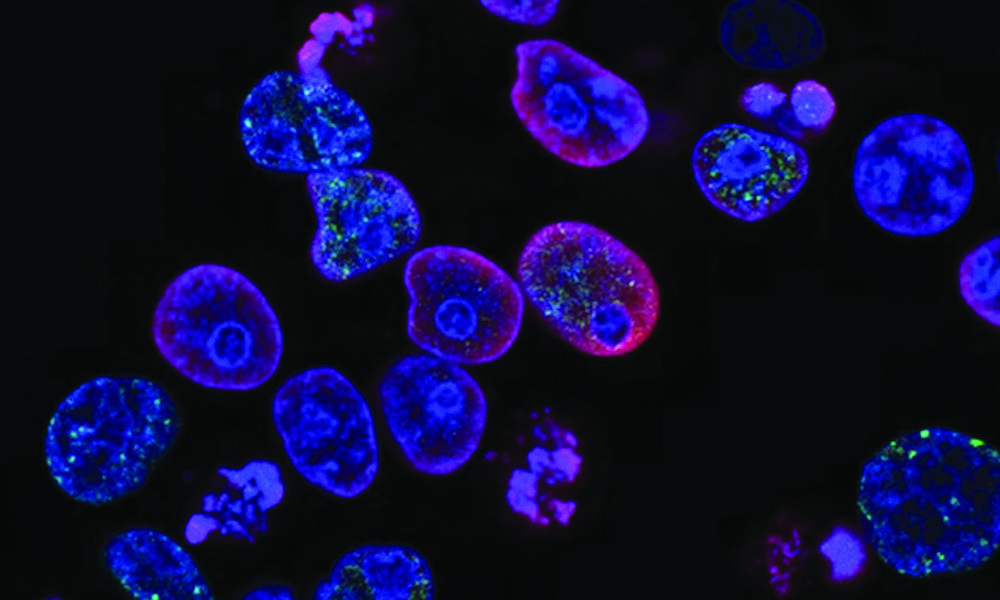

Most of us know the statistics associated with cancer. It has touched, directly or indirectly, almost every Canadian. But thanks to the relentless work of researchers, around two out of three patients diagnosed with cancer today will survive beyond five years from their initial diagnosis—up from 55 per cent in the early 1990s. The most recent innovations in cancer treatment have stemmed from immunotherapy, a fast-growing and exciting field of study for cancer researchers.

“Cancer immunotherapy unleashes the power of the patient’s own immune system. It is today considered the fourth pillar of cancer therapy,” Sonia del Rincón, assistant professor in McGill’s Department of Oncology, said in an interview with The McGill Tribune.

Recently, University of Washington (UW) researchers developed a cancer vaccine targeting HER2/ErbB2, a protein on the surface of tumour cells which affects one in five breast cancer patients. The vaccine was shown to have minimal side effects, like fevers and fatigue, while generating a significant immune response in the non-randomized trial.

William Muller, a professor in the Department of Oncology and renowned investigator of the HER2/ERbB2 genes in breast cancer, explained in an interview with the Tribune that the paper is a phase I trial, or a safety trial, that looks specifically at a safe dose range and adverse effects.

“The concept of vaccinating patients against specific tumour targets has its roots in the early 90s when Thierry Boon’s group identified the first human [tumour] associated antigen called MAGE-1,” added del Rincón, whose lab studies novel therapies for melanoma and breast cancer.

Vaccines generally work by training the body’s immune system to recognize and attack a foreign body, called an antigen. One such antigen is the spike glycoprotein, found on the surface of the COVID-19 virus. However, because cancer occurs when our own cells grow uncontrollably, specific proteins like MAGE-1 or HER2 that are overexpressed on the surface of only cancerous cells, must be targeted. “The target [of the UW breast cancer vaccine] is unusual in that it’s the intracellular domain of HER2, which is normally not presented on the surface,” Muller said.

The outcomes that the UW researchers reported are also promising because their breast cancer vaccine did not lead to any adverse effects.

“Researchers of the study did not report any severe side effects associated with the DNA vaccine,” del Rincón said. “Patients receiving other types of immunotherapy can be at risk for severe immune-related toxicities.”

Patients enrolled in the study had an 80 per cent five-year survival rate, compared with the expected 50 per cent for patients with stages III and IV breast cancer. Of course, there is still work to do before this treatment could become widely available. The true efficacy of the approach will come from phase II and III trials,” Muller said.

When it comes to cancer research, only 25 per cent of phase II trials and 40 per cent of phase III trials succeed. Phase II trials are meant to further study a vaccine’s safety and evaluate its effectiveness, while phase III trials are meant to compare the medicine to the best treatments we have today, also known as the gold standard.

Dr. Nora Disis, the lead researcher from the UW breast cancer vaccine team, explained in the most recent episode of Freakonomics, M.D. that the rapid development of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 was in large part because its safety profile in innumerable cancer patients had already been defined.

Whether this breast cancer vaccine or other vaccines under evaluation will change the landscape of cancer therapeutics remains to be seen. But, while the Emperor of All Maladies carries on its reign of terror, cancer scientists and oncologists, like del Rincón, Muller, and Disis, continue to pursue the disease with fervour.