Summer is the time to relax, hit the beach, and for some, to get a tan. But swimsuit season brings with it a major public health risk in the form of ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Problems that range from wrinkles to skin cancer arise during the summer because this is when UV radiation from the sun is at its most intense.

According to the American Academy of Dermatology Melanoma, melanoma is the second-most common form of cancer in young adults between the ages of 15 and 29, and for 25 to 29 year olds, it’s the most common type.

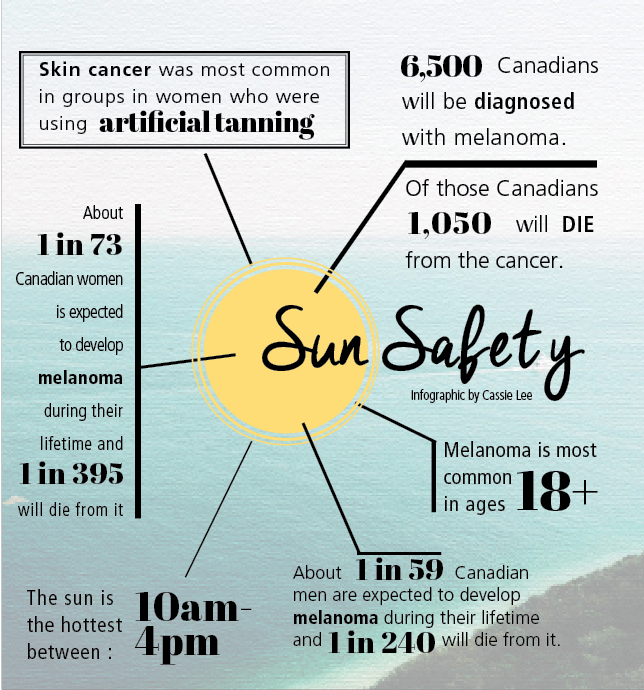

“This is not a cancer [for] the elderly,” stated Dr. Ari Demirjian of the Montreal General Hospital. “Melanoma is common [starting] from the age [of] 18 and [is] especially prevalent in young women who use artificial tanning.”

According to the Canadian Cancer Society, approximately 6,500 Canadians are diagnosed with melanoma each year, of whom 1,050 will die—and it shows no signs of slowing. When evaluating the seven most common forms of cancer in the U.S., melanoma is the only one whose rate of incidence is increasing.

“People just don’t think of tanning as a health risk,” explained Alex Cloherty, project manager of the Tanning is Out Challenge at The University of British Columbia Okanagan. “We see that sun-kissed glow as a healthy thing. However, any change in skin colour means that your skin has been damaged.”

To see why sun exposure is so damaging, it’s important to understand what happens when humans are exposed to UV radiation. UV radiation falls into a part of the electromagnetic spectrum called ionizing radiation, which means that it can break chemical bonds like those found in DNA, a process known as photoaging.

“Basically, the UV rays damage the DNA in the cells of the skin,” explained Demirjian. “[This can cause] photoaging, and depending on what part of the DNA is damaged, can lead to cancer.”

But DNA damage is not unique to skin damage; the World Health Organization lists sun exposure as a major risk factor in cataracts, the world’s leading cause of blindness.

To help prevent these problems, scientists have developed sunscreens that reflect or absorb UV rays and convert their energy into heat, rendering them relatively benign. While the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends wearing sunscreen with an SPF of at least 15, higher is not always better.

“Let’s take an SPF [of] 60 [or] 30,” Demirjian said. “There’s only [a] two percent difference in overall protection regarding both of those SPFs, so it’s not really double the protection. The reason we suggest 60 for people with skin cancer […] is because people don’t put enough sunscreen on their skin, so even though they think they’re applying 60, due to lack of quantity and not reapplying, they’re not actually getting [the] protection [that] they think [they are].”

And it’s not enough to just apply it once a day.

“Sunscreens have to be reapplied every two hours,” Demirjian said. “What we recommend is between two to four tablespoons on [the] whole body, depending on the size of the individual.”

Consumers should also ensure that their sunscreen protects from both UVA and UVB rays, known as broad-spectrum protection. This accounts for the two types of UV rays, A and B, which are responsible for sunburns—UVA—and aging and tanning—UVB. Because SPF refers only to a sunscreen’s ability to block UVA rays, even a high SPF might not fully protect against long-term skin damage.

While this mentality of protecting from the sun holds exceptionally true during the summer, it’s important to realize that the sun is always present.

“We’re not in the sun only when we’re on the beach,” Demirjian said. “Even […] on campus at noon, one still needs to use [sunscreen].”