Over the course of the last 15 years, airport-goers have seen huge changes in the processes required before boarding a plane, particularly the stringent security measures to which all passengers are subjected. Little is known, however, about not only how these machines work, but if they do make a difference in the safety of travellers.

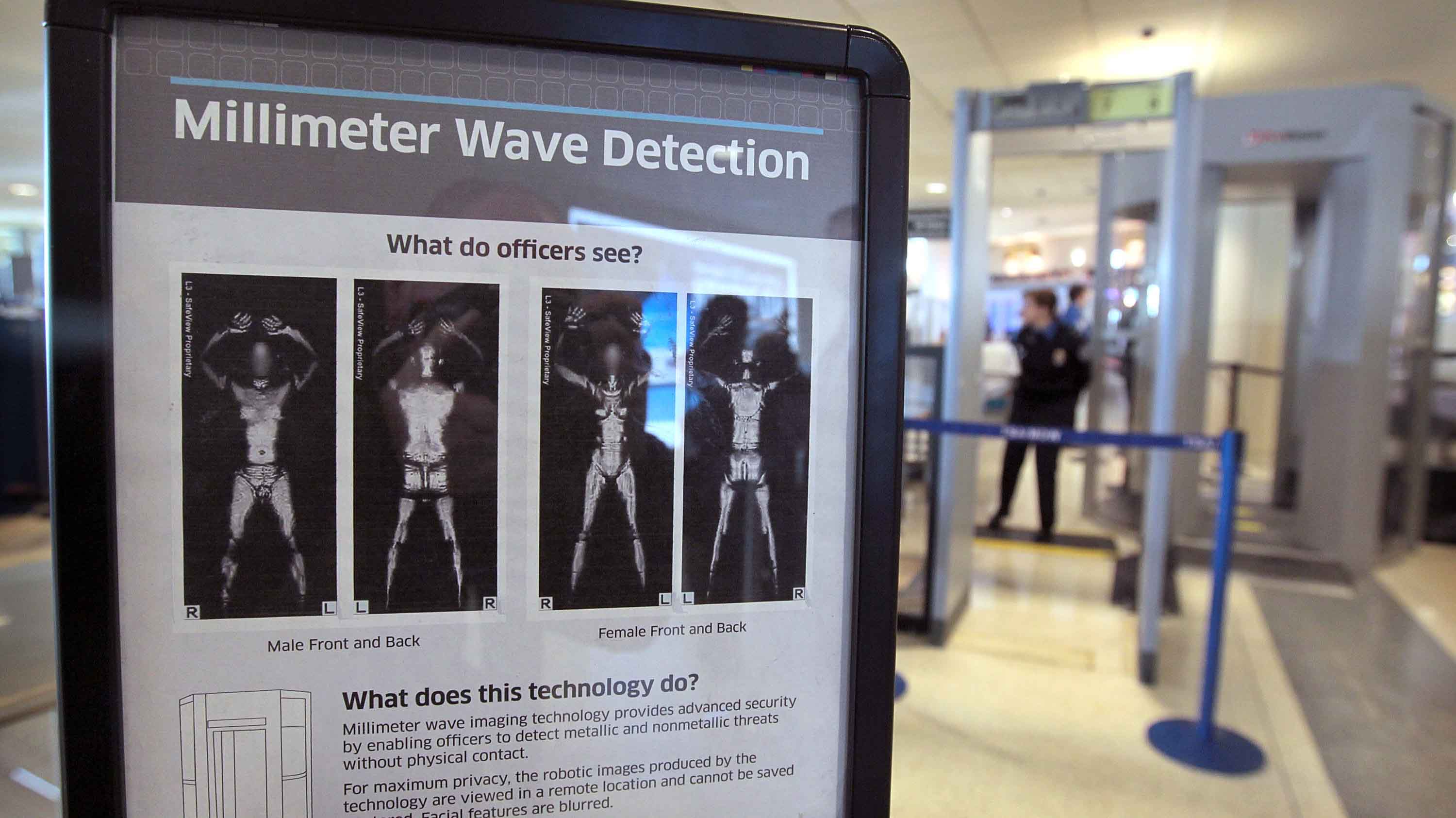

One relatively new addition to airport security is the full-body scanner. There are two types of scanners: Millimetre wave and backscatter. Backscatter scanners employ low-energy X-rays, whereas millimetre wave scanners transmit radio waves over the person being scanned and measure the amount of energy reflected back. With these techniques, body scanners are able to detect metal and non-metal weapons and explosives, including those made of plastic. While full body scanners may appear to be an invasive procedure, the agents working at security are not privy to the full results. The security officer who views the scanner image does not actually see the passenger in question, the scanners either blur the faces or display the passenger’s body as a chalk outline in the depiction. Furthermore, the results are not stored and cannot be printed. According to the TSA, the millimetre wave scanners generate less energy than a cell phone, and backscatter scanners produce radiation equivalent to what a person would receive after sitting for two minutes in an airplane.

The question of whether machines, like the full-body scanner, do more harm than good, shadowing any annoyance that they might pose to passengers, has been up for debate for some time. In the United States, a report released in May 2015 by the Department of Homeland Security claimed that the Transportation Security Agency (TSA) had not been adequately maintaining its airport screening equipment, partly by not issuing any policies requiring airports to designate maintenance-related responsibilities to their employees. Without proper maintenance, screening machines are more likely to break down without warning, and if the machines are not operational or defective, it could potentially put more than a handful of the 1.8 million passengers screened daily by the TSA at risk, along with their aircraft.

Meanwhile, here in Canada, the Canadian Border Services Agency announced last week that they are planning on implementing facial-recognition technology to compare the images of passengers arriving in Canada with photographs of suspected terrorists and other criminals on watch lists; however, according to Canadian Privacy Commissioner Daniel Therrien, these machines could yield “false positives” in the faces of people who bear an unfortunate resemblance to those on the watch lists and cause them to undergo an unnecessary secondary screening.

Both US and Canadian screening policies and equipment have faced criticisms. Airlines force travelers to surrender their privacy and convenience without guaranteeing their safety. Nevertheless, the security screening process does not look like it will be changing any time soon. No matter what reservations passengers have about the nature of airport security, it is and will remain an unavoidable part of flying.