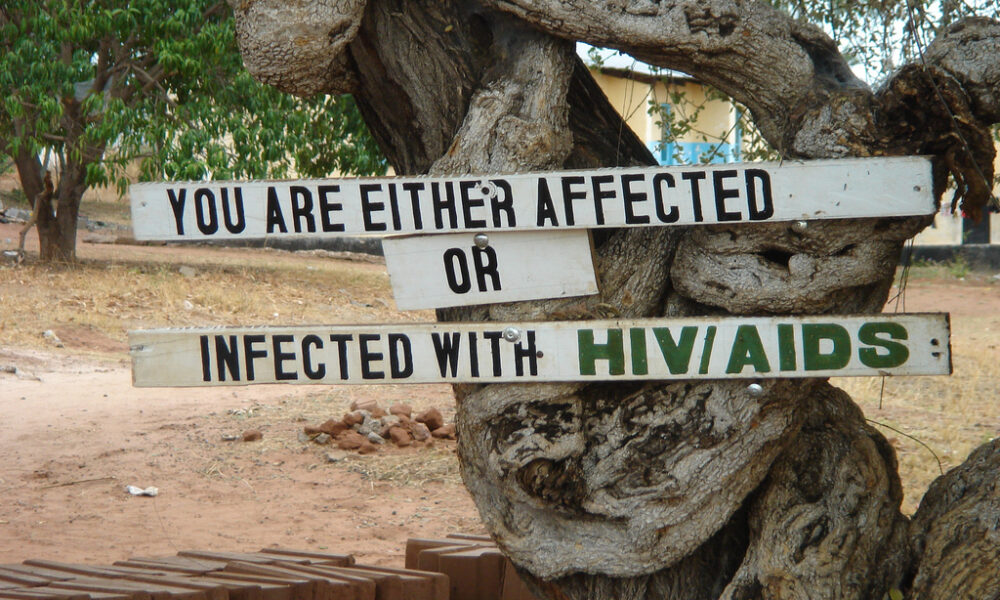

Four decades into the HIV epidemic, the world is still struggling to keep the disease under control. While countries in the Global North have benefitted from access to life-saving drugs, those in the Global South have had to contend with exorbitant prices, barriers to access, and little help from pharmaceutical companies.

In 2021, approximately 38.4 million people were living with HIV—54 per cent of them were women and girls. The geographic distribution of HIV cases also disproportionately affects sub-Saharan Africa, where two-thirds of patients with HIV can be found. Young women in the region are twice as likely to contract HIV than young men.

Despite the plethora of research available to the public and the significant decrease in HIV prevalence, too many people still lack comprehensive sex education and accurate information, thus overlooking feasible precautions, putting off HIV diagnoses, and impeding subsequent treatment.

In a recently published paper in The Lancet HIV, researchers from McGill and other institutions looked into how intimate partner violence (IPV) has affected rates of recent HIV infection and HIV treatment in the past year. They found that to stay on track with the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) goal of ending HIV as a public health threat by 2030, the inequities women face in education, safety, and health services must be addressed.

The research team conducted a pooled analysis of nationally representative surveys with data on IPV and HIV across countries in sub-Saharan Africa such as Uganda and South Africa. They looked at data from 57 surveys spanning 20 years and 280,059 women across 30 countries.

However, identifying the effects of IPV on women’s HIV risks comes with its own inherent implications.

“First, the relationships between IPV and HIV acquisition in women, and women’s engagement in HIV care are extremely multifaceted and complicated,” lead researcher Salome Kuchukhidze, PhD candidate in McGill’s Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Occupational Health, wrote in an email to The McGill Tribune.

“This is why it is difficult to ensure that we account for all the external factors or variables that might influence HIV and IPV individually and thus might muddle the true relationship between the two.”

Despite the onerous undertaking, Kuchukhidze explained that the team carefully maintained excellent statistical sampling throughout their analysis, which allowed them to identify a clear correlation between IPV, HIV, and a woman’s physical and mental well-being.

The researchers concluded that women are particularly vulnerable to HIV. Adding onto inherent biological risk factors, women experiencing IPV are often in relationships with abusive men who have additional sexual partners without their partner’s knowledge, ultimately increasing their risks of contracting HIV. Kuchukhidze’s team also found that the imbalance of power in cases of IPV is correlated with difficult contraceptive-use negotiation—when women are coerced or bullied into forgoing contraception—which further exposes them to sexually transmitted infections.

“We show that women who had experienced physical or sexual IPV were over three times as likely to acquire HIV recently than those who had not experienced IPV in the past year,” Kuchukhidze wrote. “These women also had worse HIV treatment outcomes.”

Kuchukhidze believes that more research into the connection between IPV and HIV, among other social and medical variables, is necessary if governments hope to understand the causal relationship between the two.

“Given this link, governmental (or non-governmental) funding for HIV interventions should incorporate aspects of IPV prevention and eradication, as well as additional support for women living with HIV who are experiencing IPV,” Kuchukhidze wrote.

By highlighting this link, Kuchukhidze’s researchers have discovered a path forward: To truly eliminate HIV as a public health threat in sub-Saharan Africa, IPV must be considered as a mitigating factor when providing care to women and girls.