The cells in our bodies perform functions that have yet to be fully understood. These structures which have existed for two billion years continue to baffle the scientific community. The mitochondria, an organelle with many unique features and functions, has been a topic of widespread research ever since its discovery in the late 19th century.

Continuing this long tradition of investigating the mysterious mitochondria, Professor in the Department of Biochemistry at McGill Nahum Sonenberg and his team of researchers have uncovered a mechanism through which the mitochondria plays a key role in preventing cell death in the absence of sufficient nutrients.

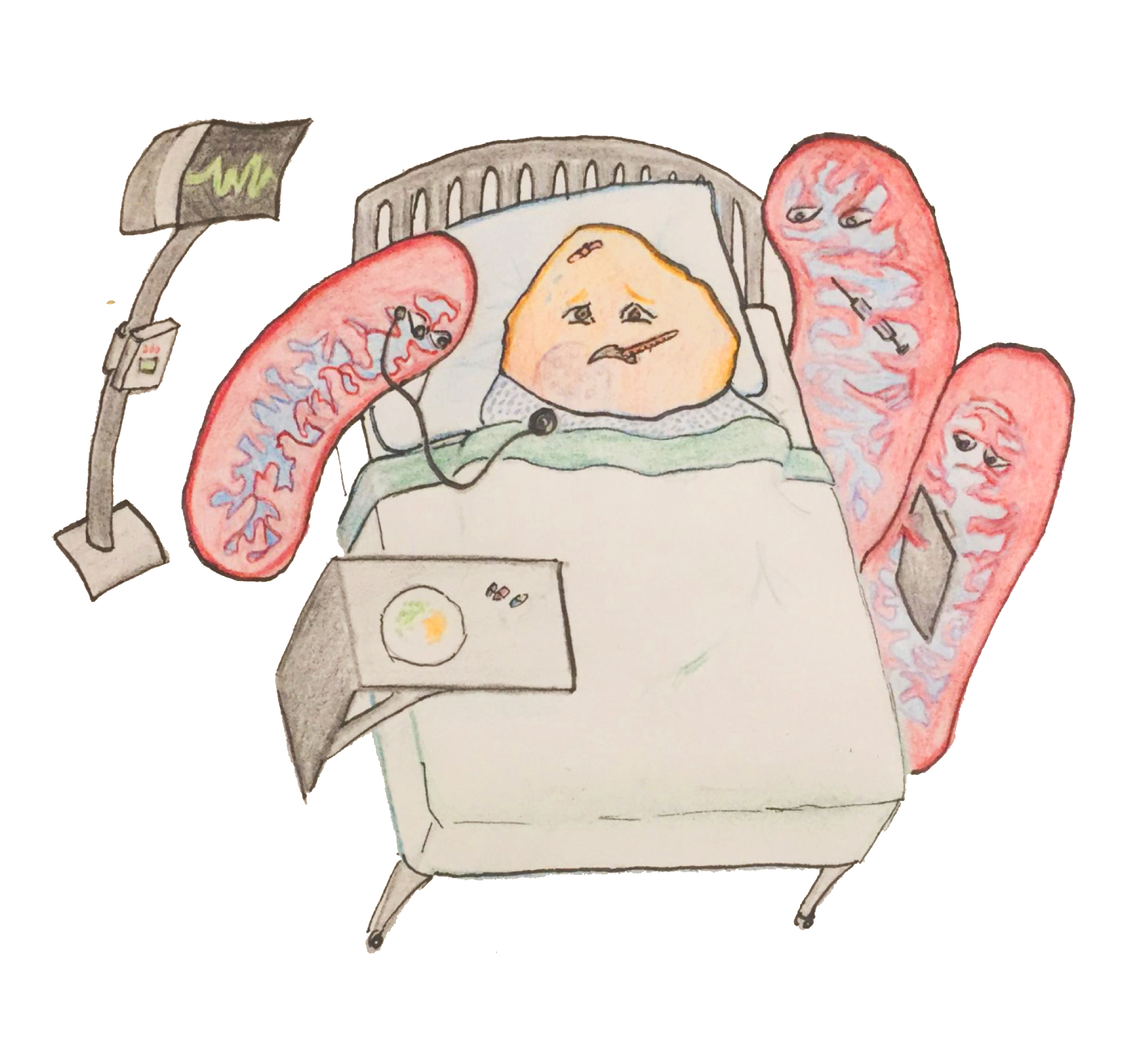

Mitochondria have already gained celebrity status among organelles. Aside from synthesizing Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP)—a molecule that provides energy to cells—the mitochondria is responsible for many other functions, including thermal heat production in various mammals during early life stages and hibernation. They work as coroners, allowing cells to die when it becomes necessary to make room for the formation of new tissue. They even serve a neurological function—storing scores of calcium ions to be used in regulatory processes and in the transmission of information from neuron to neuron.

John Bergeron is a professor in the Department of Medicine and co-director of one of the two McGill laboratories which took part in the recent study. Along with Heidi McBride and her team from the Montreal Neurological Institute, he played a key role in Sonenberg’s success in isolating important information about how the mitochondria aids in the functioning of a cell. MTOR, a type of protein enzyme, serves as a core component of two protein complexes which have the ability to regulate cellular activity.

“The paper represents a discovery linking mitochondrial function to the master sensor of cellular nutrients, and regulator of growth in cells known as mTOR,” Bergeron said. "mTOR senses nutrients, insulin and growth factors, and translates this information to a downstream cascade of events that increase cell growth, metabolism and cell replication.”

When mTOR is blocked, the loss of the protein triggers the mitochondria to produce more energy, which is essential for cells to survive under low-nutrient conditions. This is where Sonenberg’s new research deviates from the previously known knowledge of the enzyme.

“[Sonenberg] originally discovered that this process was tightly regulated through protein synthesis initiation factors,” Bergeron said.

Initiation factors signal the beginning of translation (the first step in protein synthesis) and are under the control of mTOR.

The McGill team’s work embodies the next generation of cutting-edge biochemical research, which uses advanced testing methods at the microscopic level that enable rapid testing of mitochondria to view alterations in cells. This type of work has become a “hallmark” of Sonenberg’s methodology, according to Bergeron.

Beyond Sonenberg’s advanced research techniques, the professor is helping biochemists across the world come closer to deeper understanding of the multi-billion year-old organelle.

“The uncovering of a mechanism is always a goal of fundamental basic research in biology,” Bergeron said. “Filling in further details as to exactly how [mitochondria] divide and send signals to make these life and death decisions for cells is a challenge that only can be met by more detailed research. The work has immediate ramifications since the mTOR inhibitors touched upon in the paper are the basis for a new generation of drugs currently under test for cancer therapy.”

The effects of the study could be far-reaching.

“The integration of mitochondria into the life of cells has evolved over the past billion years or so with more surprises sure to be found that will advance human knowledge with hoped for benefits to health and disease prevention,” Bergeron said.