In 1957, the boundaries between Earth and space were first breached: The USSR launched the satellite Sputnik into space, marking the first contact between humans and our galaxy, setting off the aptly named space race between the Soviet Union and the U.S.

Even after icy international relations began to thaw with the end of the Cold War, the space race continued and extended its pool of competitors to other countries. From the rapidly expanding economies of Japan and India to private, Musk-esque ventures, the fight to monopolize the mysteries of the heavens has become crowded. What many of these powers have in mind, though, is uniform—to reach the notoriously treacherous Martian landscape.

The Polar Microbiology Laboratory at McGill, however, has set out to deepen our understanding of the Red Planet from the comfort of home. Rather than rushing off into space like seemingly every billionaire today, researchers at the lab are looking to Earth’s most inhospitable environments in an attempt to find lifeforms akin to what might be present on Mars. In a new paper spearheaded by Elisse Magnusson, a PhD student in the Department of Natural Resource Sciences under the supervision of professor Lyle Whyte, the lab team describes their research on microorganisms living in Lost Hammer Spring, one of the coldest springs on Earth and an analogous habitat to the life theorized to inhabit Mars.

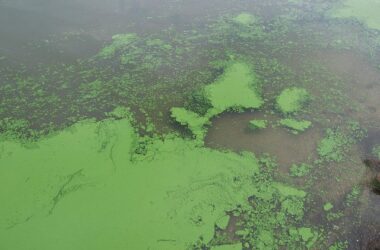

Lost Hammer Spring, in Nunavut’s most northern area, is known for its high salinity—over 20 per cent salt concentration. High salinitykeeps the water liquid, even in below-freezing temperatures. Researchers view Lost Hammer Spring as one of the closest terrestrial environments to Mars, with its cold salt springs and large salt deposits being theorized to also exist on the Red Planet.

Mars is home to both organic carbon—which plants, animals, and most microorganisms need to survive—and environments rich in inorganic material, or matter not principally composed of carbon.

According to Magnusson, Lost Hammer Spring is indeed one of Earth’s most Martian environments. By learning how microorganisms survive in these environments and the effect they have on their surroundings, researchers can better predict what they should be looking for on Mars.

“The types of location or metabolism that we can expect to see [are] expanded [by looking to inorganic environments],” Magnusson explained. “It is also important […] so we know where exactly we might want to look and what exactly we might want to look for because certain types of microbes and metabolisms mean particular biosignatures.”

The team’s acquisition of a metatranscriptome, or the isolation of the total mRNA present in each microorganism, is especially remarkable; it provides information on the genes that these special microorganisms express. Using this technique, the Polar Microbiology Lab gleaned important insights into how these microorganisms can survive in such inhospitable conditions and what materials they consume and recycle.

Magnusson was enthused by this discovery, adding that it allowed researchers “to look at what genes [the microorganisms] are expressing and look with much greater detail at their metabolism, their adaptations.”

The European Space Agency has even shown special interest in the team’s research. The group turned in their results to the agency, which is planning to use the findings to calibrate life-detection technologies.

The team’s research demonstrates the fascinating connection between the extraterrestrial and terrestrial, as well as intriguing developments in the search for alien life. Although space exploration is a requirement to prove any theories posited by this research, important discoveries can be made without leaving orbit. In fact, it is curious that our home planet is often just as alien as Mars.