The Killam Seminar Series hosted a seminar about inflammation in multiple sclerosis (MS) at The Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital (The Neuro) on Oct. 31. The seminar series invited Roberta Magliozzi, associate professor from the University of Verona, Italy, as part of The Neuro’s goal to bring in exceptional guest speakers from around the world.

MS is an autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation in the brain and spinal cord. The body’s own immune cells, including B cells and T cells, erroneously target and damage a fatty insulating substance called myelin, mistaking it for a foreign invader.

“Most of the [inflammatory] cells we found were in the stroma [located in the centre of bones, i.e. bone marrow]. The only cells we found within the blood vessels [were] granulocytes and neutrophils,” Magliozzi said. “Our idea is that the inflammation persists in some niches […] hiding in the brain, especially in the progressive forms.”

Myelin is a material that wraps around and electrically insulates axons—the long, thin extensions of neurons responsible for transmitting information within the brain and the spinal cord. MS-associated myelin damage, along with direct injury to the neurons themselves, leads to a range of distressing symptoms, including changes in sensory perception, movement, and cognition.

The average age of MS diagnosis typically falls around 43, although the onset can occur anywhere between the ages of 20 and 50. Alarmingly, Canada has one of the highest MS diagnosis rates worldwide, with over 90,000 people living with the disease, meaning nearly one in every 400 Canadians has received an MS diagnosis.

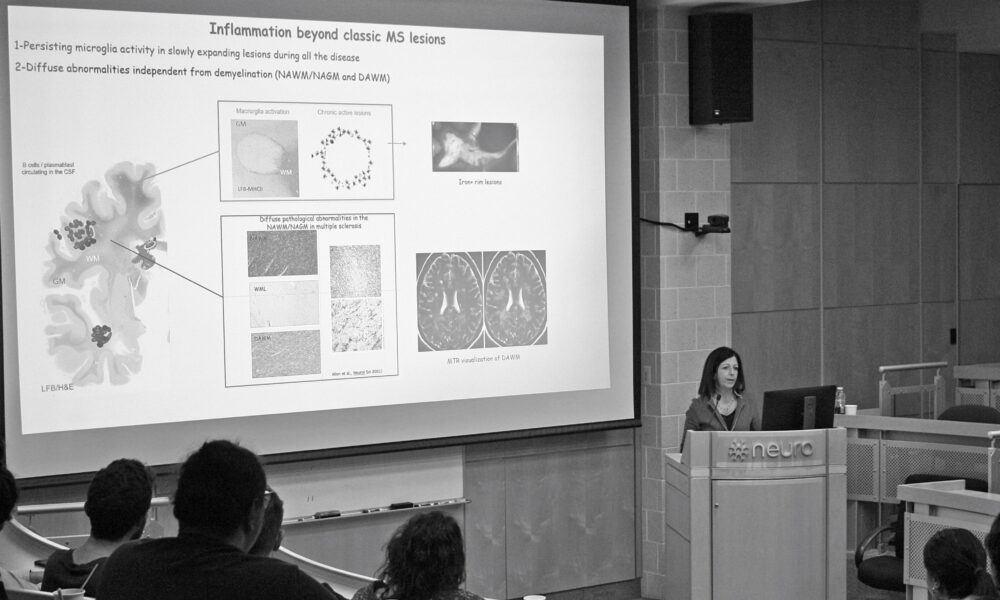

Magliozzi’s research centres on investigating the immunopathological mechanisms underlying MS. Her primary aim is identifying intersecting pathways of the nervous and immune systems, as well as potential biomarkers associated with the progression of MS. The ultimate goal is to enable early detection and intervention and to personalize treatment strategies that could slow or halt the progress of the disease. Magliozzi emphasized the central role of inflammation in MS.

“Inflammation is consistently associated with chronic neuronal degeneration,” Magliozzi said.

Although recovery of the damaged myelin and the axons can occur during the early stages of the disease, MS reaches a ‘progressive’ stage as relapses occur, during which neurons experience irreversible loss of function, leading to deteriorating symptoms over time.

One of Magliozzi’s pivotal findings revealed that patients with meningeal inflammation, which affects the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, and an early disease onset, tend to experience early disability onset.

“We found that progression with meningeal information and early age of onset [translates to patients having] a short disease duration and they also die early,” Magliozzi said.

Researchers from the University of Vienna, Austria, and the Mayo Clinic in the United States, validated this groundbreaking discovery using biopsy samples that demonstrated the presence of elevated meningeal inflammation and severe pathology in the cerebral cortex.

“We have now examined many MS cases in the UK, MS tissue bank, and this has started being validated by other groups,” Magliozzi said.

Magliozzi’s work also showed that MS lesions—areas affected by the disease—tend to cluster around the ventricles and that the onset and progression of MS are associated with increased levels of fibrinogen. Fibrinogen, a clotting factor, triggers microglia—the brain’s immune cells—leading to heightened inflammation. In one of the graphs illustrating these findings, neurons and microglia contain a significant concentration of fibrinogen.

“There is a high correlation between neuronal loss or axon loss and microglial activation. So, this means that there is a strong association between these phenomena,” Magliozzi explained. “And then there is this very elegant study from a Dutch and UK group, where they showed that the meningeal inflammation in MS induces […] not only activation but also phenotypic changes in vertebral microglia, which is then directly associated with increased neural degeneration.”

While a definitive prevention or cure for the disease is yet to be discovered, the unwavering dedication of researchers and healthcare professionals brings us closer to a future where MS may no longer be a life-altering diagnosis.