The human brain is an extremely complex organ that is the integrating and processing centre of the body. It helps people recognize faces, remember complex formulae, and produce emotions. Many of these reactions rely on the brain’s ability to correctly process information through its visual system. As intelligent as the brain may be, under the right conditions, it can still be tricked.

The eyes can be thought of as a satellite that receives visual information from the environment and transmits this data to the brain, like a television receiver. To do this, the eye processes in visual data through specialized light-sensitive cells called rods and cones which are located on the back of the eye—the retina. This information is then sent to the brain through a mass of cells that form the optic nerve. Most of the cells of the optic nerve transmit information to a structure in the brain known as the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus (LGN), which then relays information to the visual cortex at the back of the brain, known as the occipital lobe. This is where the brain processes the information that had been taken in from the eyes.

Despite this, the visual cortex can be tricked into ‘seeing’ something different from what the eyes actually ‘see,’ explained McGill Associate Professor Erik Cook from the Department of Neuroscience, whose research focuses on how neural activity underlies conscious visual perception.

“Over millions of years, our visual system evolved in an environment that was pretty stable,” Cook explained. “So it sort of cheats, takes advantage of the prior knowledge of the system, and takes shortcuts. What a visual illusion [really] is, is an image that the visual system was not designed to see; when it tries to take shortcuts, it fails. [This] reveals the algorithms the brain is trying to use.”

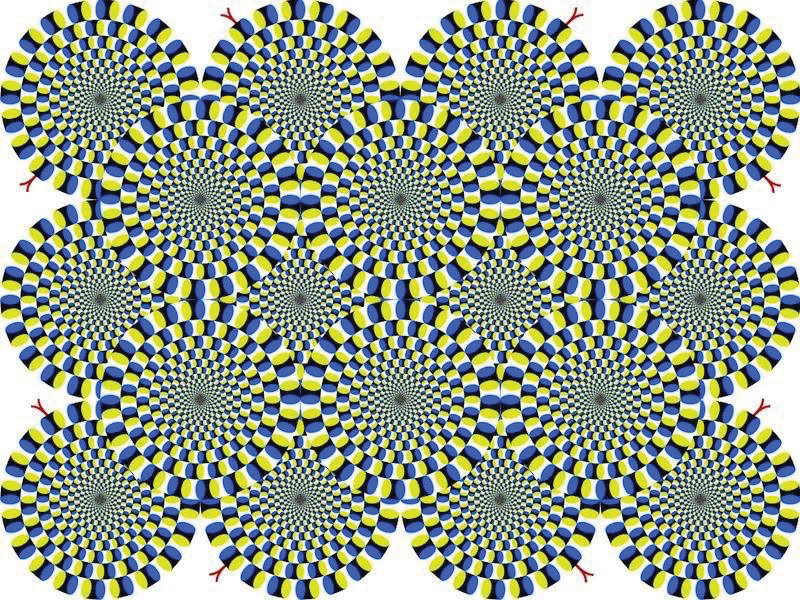

In photo one, it seems that the wheels are rotating, even though they actually are not. This geometric illusion—known as the Rotating Snakes Illusion—was developed by Kitaoka Akiyoshi.

Illusions like this one work because the visual cortex is fooled into believing something that isn’t actually happening—like the wheels moving—is happening.

“The first thing to notice about ‘Rotating Snakes’ is that the motion grinds to a halt if you stare at just one part of the image,” explained vision scientist and SUNY College of Optometry Professor Ben Backus in an interview with NPR. “On the other hand, it keeps going if you keep looking around.”

This can be explained by how the eye moves under special conditions. Small and quick changes in the eye’s position, known as saccades, causes neurons to start rapidly firing. This overwhelms the visual cortex, making the wheels appear to be in motion.

“As your eye moves, it is the particular pattern on the page that stimulates motion sensitive detector cells in your brain [which] are in the cortex,” explained Professor Frederick Kingdom from the Department of Ophthalmology. “It tricks those cells into thinking that this is movement. The cell doesn’t care where it’s activation comes from. When it’s activated, [it thinks] that there’s movement.”

In photo two, the brain interprets the circles as spheres coming out of the page or going into the page. This is because the visual system uses light to interpret the position and space of objects. The brain is conditioned to expect light from a single source, shining down from above (like the sun). This leads it to believe that these shading patterns could only have been caused by light shining down on the sloping sides of a dome—coming out—or the bottom of a hole—going in. Though the shape is drawn on a flat piece of paper, the brain automatically interprets it as a 3-D object, because of the shading.

Moreover, cells within the visual system can fill in the breaks in lines or shapes—without any other input—using the assumption that an object belongs there.

“There are different ideas about the Kanizsa triangle,” Kingdom explained. “One is that the ‘pac-men’ [shapes] stimulate a triangle detector in your brain.”

Essentially, there are specialized cells in the brain that selectively detect shapes. These cells are found in the infra-temporal cortex, which is also in the recognition of familiar things like faces, objects.

“Some of these cells might be being stimulated by the Kanizsa Triangle [to create that illusion],” Kingdom said.

However, other theories have been presented.

“[When] your brain sees something with corners, it tries to fill in what would be there to produce such a pattern,” Cook explained. “You see corners all the time and corners correspond to edges. [The brain thinks] since there’s corners here, there must be some kind of object. ”

To survive, humans have been hard-wired to trust their instincts. But in the modern world, there can be more than meets the eye, and an understanding of the brain’s circuits can lead to the manipulation of these inate responses.