Death has an equalizing, inevitable force. But the pandemic, like all public health crises, has cast the sword of Damocles in sharper relief than ever, and indiscriminately so. Yet while the blade will always fall, few reflect on the science of it—what really happens to our bodies after we die?

The McGill Office for Science and Society (OSS) hosted day one of two of the 2021 Trottier Public Science Symposium on Oct. 25, with its central theme being the science of life and death. Headed by director Joe Schwarcz, the annual lecture series brings in leading experts to disseminate scientific knowledge in their respective fields and to fulfill the OSS mandate of “separating sense from nonsense” amid a deluge of falsehoods.

Dr. Paul Offit parses through vaccine misinformation

Paul Offit is a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania and a director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania. Having appeared as an expert guest on CNN only an hour before, Offit began his informative lecture with some statistics about herd immunity. He explained that in order to predict the herd immunity threshold, the contagiousness index—the number of people infected per one positive case—is divided by the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing contagion. In the case of COVID-19 in the U.S., this is around 90 per cent.

“I think we still need to vaccinate about 40 million more people in the United States if we really want to achieve herd immunity,” Offit said.

As a member of the FDA vaccine advisory committee, Offit receives many emails spouting vaccine misinformation in an attempt to dissuade him from encouraging vaccination. On Oct. 26, the committee is set to discuss whether the vaccine should be approved for 5 to 11-year-olds in the U.S.

Offit took the audience through several of the most common myths about the COVID-19 vaccines, such as claims that they decrease fertility or alter a recipient’s DNA. If the first myth were true, Offit explained, then the U.S. birth rate would have decreased significantly since the vaccine rollout began. The mRNA vaccines cannot change DNA sequences because the pieces of RNA are unable to enter the cell nucleus or to be reverse-copied into DNA.

Offit debunked several more unfounded claims, including one that asserted that vaccines can make humans magnetic. The draw of pandemic conspiracy theories, like those touted in media such as Plandemic, is that individuals can put the blame on a common scapegoat and avail themselves of personal responsibility.

“A pandemic is chaos. There is so much that is unknown when it first [starts],” Offit said. “What [conspiracy pieces] do is make order out of chaos. They give you a villain, and give you a sense of order even though it’s completely wrong.”

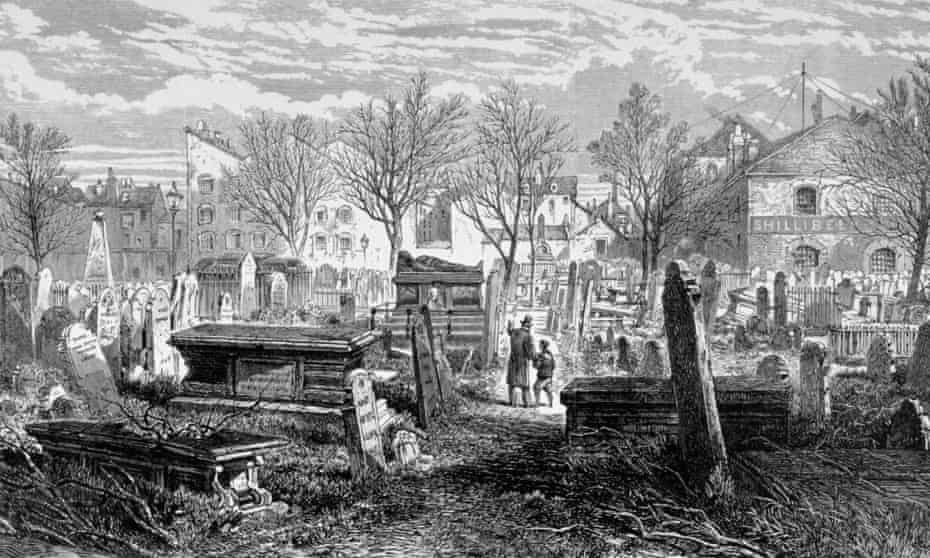

Mortician Kari Northey explores the science of corpse preservation

Licensed mortician and Youtuber Kari Northey has been in the business of bodies for more than 20 years, and has received a fair share of morbid inquiries about her career. In her captivating presentation, Northey took attendees through the history of the mortuary field and addressed the most common questions about caring for the dead.

“Embalming is more than injecting formaldehyde [and] draining out blood,” Northey said. “It’s preserving in various ways to allow viewing, funerals, and gatherings of family.”

Proteins denature during the biological process of death, leading to decay, but embalming fluid stops this process from occurring. Though formaldehyde was only introduced in the 20th century, the early origins of embalming stretch back to Ancient Egypt, with the use of natron, a mixture of soda ash and baking soda, on bodies before mummification.

Northey walked the audience through the embalming process, including the not-so-pleasant details of cavity drainage, which replaces the material in the abdomen—containing the bacteria that are decomposing the body—with preservative fluids.

Despite their gloomy job description, morticians can act as magicians by physically restoring the deceased so that they are made “viewable” for family members.

“It’s really an illusion of the person that we’re creating for family to connect with for that final moment,” Northey said. “Even if the person’s not perfect, they may be perfectly recognizable.”

Northey closed by noting how the field has adapted to contemporary issues. Environmentally friendly options for the deceased, such as “aquamation” and green burials, are becoming increasingly popular.

“There’s now more women going into the field than there are men, there’s now funeral homes that look drastically different than they used to,” Northey said. “The face of the business is constantly changing with the times, which is beautiful to see.”