El Niño has been the latest buzzword explanation for Montreal’s—and the world’s—unseasonably warm weather.

Normally, the prevailing wind patterns in the Pacific Ocean, known as trade winds, blow east to west. When these winds are weaker than usual, a buildup of warm and wet weather along the West Coast of the Americas and drier conditions in Indonesia and Australia occurs, known as El Niño. Conversely, when the cycle enters a cooler phase, marked by stronger winds, it is known as La Niña.

Part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, the two terms are used by weather scientists to describe specific temperature and atmosphere conditions in the Pacific. Because El Niño is connected to many other wind currents, any changes in the system can dramatically alter global weather patterns. For example, the ‘super El Niño’ of 1998 resulted in frequent and severe ice storms that devastated parts of southern Quebec.

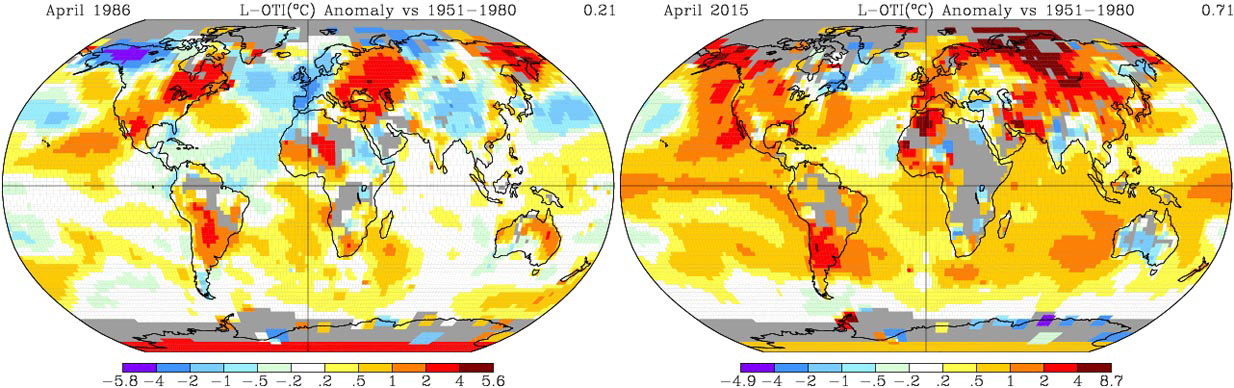

Predicting the effects of an El Niño, however, is difficult. While El Niño is not caused by climate change as it is a naturally occurring phenomena, a changed climate means that the impact of an El Niño is becoming greater and increasingly unpredictable.

For example, an ENSO cycle generally takes place every two to seven years, although a 2014 paper published in Nature suggests that climate change will likely bring about an increased frequency of extreme El Niño events.

Recently published data collected by Environment Canada reports that the average temperature in December 2015 was 1.65 degrees Celsius. The average temperature in December 2014 was -3.45 degrees Celsius—a difference of over 5 degrees.

While these differences are dramatic, it’s important to note that they cannot be directly correlated with the El Niño. Rather, the weather system is likely a contributing factor to the latest of Montreal’s abnormally pleasant winter temperatures.

On Jan. 7, United Nations (UN) officials warned of the effects of the anticipated intensified 2016 El Niño. Stephen O’Brien, the UN under-secretary-general for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, urged the international community to prepare for the changed weather. O’Brien cautioned that combined with the impacts of climate change, the 2016 El Niño phenomenon is pushing into “uncharted territory.”

While El Niño may have favourable effects on some areas, such as a potential amelioration to the endemic drought in southern California, in many other areas of the world dramatic weather events are expected to cause humanitarian emergencies. Already, there have been intensified drought conditions throughout Eastern Africa, notably affecting Ethiopia. Projections for 2016 predict that food insecurity will affect 22 million people across the region, and at this moment, 10.2 million people are in need of emergency food assistance. Additionally, El Niño increases the possibility of typhoons and cyclones occurring, which will affect countries throughout the Pacific.

ENSO cycles rarely last longer than one year, but their impact has no end-point. And because El Niño events are often associated with droughts, O’Brien anticipates high levels of food insecurity throughout the Caribbean and Latin America.

“The impacts, especially on food security, may last as long as two years,” he explained.

Montreal’s latest mild temperatures are expected to persist throughout February. Long-term forecasts predict mild winter conditions across Canada with less persistent and less intense cold spells compared to those that have dominated the past two winters. The unseasonal rain that has replaced Montreal’s usual winter precipitation is likely an effect of this year’s particularly powerful El Niño event. While precipitation patterns are expected to remain relatively normal, it is difficult to predict what form the precipitation will take; this will likely result in less-than-ideal ski conditions.

“Every El Niño event is unique unto itself,” explained Chris St. Clair, a weather broadcaster for The Weather Network. “This El Niño will weaken in the coming months.”

While the 2016 El Niño has so far led to many atypical weather events across the globe, there is reason to believe that the weather patterns will return to normal in the later half of the Canadian winter. There is preliminary evidence that the Pacific Ocean temperatures are already beginning to cool, leading many meteorologists to believe that the wackiest of El Niño weather-related events are behind us.