Diseases are one of humanity’s greatest blind spots, an enemy that always reappears. Fears of loss and death can lead to dramatic societal turmoil, from economic troubles to civil unrest. They remain, however, pivotal moments in history, providing valuable opportunities for comparisons between past and present disease management tactics.

A team of archaeologists were recently called to document the remains of a 19th-century church discovered by construction workers underneath a parking lot in the district of Sainte-Rose, Laval. The archeologists carefully recorded the outlines of the old church, cemetery walls, and graves in what was once the churchyard.

Interestingly, the team observed that the graves were small, tightly packed, and located quite close to the surface. By accessing the cemetery’s records, which spanned from 1788 to 1890, they learned that over 7000 people were buried in the small plot, primarily children less than a year old. The archeologists also noticed an intriguing spike in deaths on two occasions, in 1832 and 1834. Archeologist Justine Tétreault tied these spikes to dates in the church records.

“Well, we know the exact numbers [of burials] through records, but what we saw on the site is a very high density of burial pits,” Tétreault said in an interview with The McGill Tribune.

In fact, the 1830s were pivotal in the history of public health in Canada. In 1832 and 1834, two cholera epidemics swept through North America, causing mass casualties in Lower Canada—now Quebec and Labrador.

Cholera is a gastrointestinal disease caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Highly infectious, it causes diarrhea, massive dehydration, and is often deadly. In the early 1800s, however, the cause of the illness was still unknown.

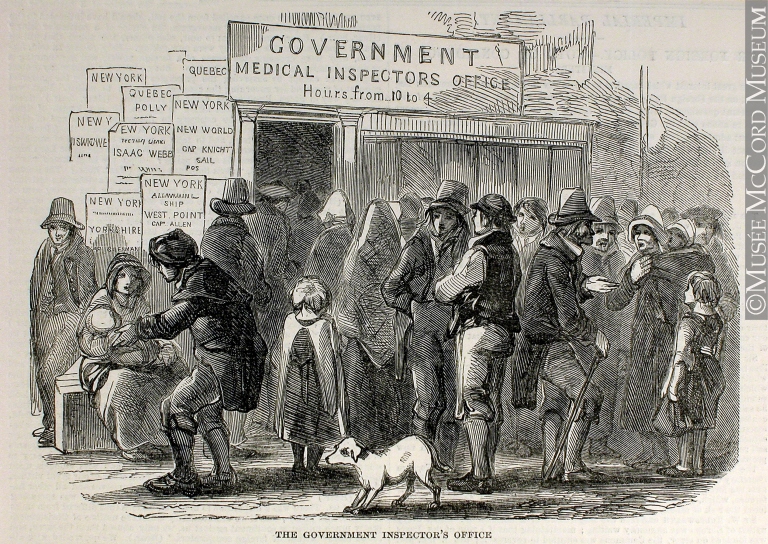

In the winter of 1831, government officials in Lower Canada learned that cholera had hit the British Isles and could spread to Canada. This information effectively prompted the birth of Canadian public health legislations, culminating in Canada’s first Quarantine Act in 1872. The famous Grosse-Île quarantine station was established during the 1832 epidemic to mitigate the impact of cholera’s arrival.

Despite these newly implemented measures, the illness’s toll was devastating. Cholera claimed over 5,000 lives in Lower Canada alone, a significant loss for a region with a total population of only 500,000 residents at the time. Jean-Philip Mathieu, a PhD candidate in the Department of History and Classical Studies, noted that fear was prevalent in the population at the time.

“It was a catastrophe for human health. It was absolutely catastrophic,” Mathieu said in an interview with the Tribune. “This was a major fear for people. It strained the system of proper Christian burials because the mortality rate doubled over a few months.”

Frightened and underprepared, Canadians were left to improvise. Government officials responded by creating a Board of Health, but also fired cannons and burned tar to cleanse the air—a futile effort, especially when fighting a waterborne pathogen. As with the COVID-19 pandemic of today, people dreaded the misunderstood disease, and their fear translated into a distrust of the government and other experts.

“The improvisation of trying to deal with this [pandemic is] very familiar,” Mathieu said. “People not complying, not following directives, not trusting doctors. A major thing people [thought was] that doctors [were] actually giving them cholera—there’s a distrust of expertise. There are a lot of commonalities [with COVID-19], and all pandemics have certain things in common.”

The apprehension caused by an unknown disease now seems eerily familiar. Yet, throughout history, epidemics and pandemics have always brought about two things: Tragedy and change. Many of the health measures implemented in 1832 persisted far beyond the end of the outbreak.

“This particular epidemic really changed things,” Mathieu said. “People realized how improvisational this was, and that you need better planning and better regulations because you [can’t] escape epidemic disease [….] And a quarantine station is just one example of that, of these governments with very limited tools and technologies, [and without] a very strong state structure. I think that’s really important contextually.”

History is cyclical. Every so often, we unearth glimpses of the past that help us understand similar experiences of those who came before. Today, like in 1832, it may seem as though the world lingers in a perpetual state of fear, distrust, and uncertainty. Yet, these same fears will push experts to change the face of public health, even if such changes only become visible in retrospect, 200 years from now.