To the environmentalist, urban vegetation, such as rows of trees, shrubs, or flower beds, might symbolize a small act of rebellion—a patch of nature amid a concrete jungle. Beyond enhancing a city’s aesthetics and supporting mental well-being, city greenery contributes significantly to urban biodiversity and climate resilience.

However, urban vegetation’s impact on air quality requires closer examination, especially given its seemingly positive influence, prompting research to determine how best to address this aspect of urban greening—the deliberate integration of vegetation in city settings.

A recent study in Environmental Epidemiology delves into the influence of urban trees and total vegetation on childhood asthma development. Co-authored by David Kaiser, associate medical director at Montreal Public Health and director of the Public Health and Preventative Medicine residency training program at McGill, the study focuses on the health of children born in Montreal between 2000 and 2015. It examines their exposure to various forms of urban vegetation, with linked medico-administrative databases identifying cases of asthma within this cohort.

In an interview with The Tribune, Kaiser explained that this study combined Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), a remote sensing technology, and satellite data, referring to the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), to monitor the cohort’s exposure to vegetation. This allowed researchers to distinguish between deciduous and evergreen trees, and determine the total urban vegetation in a given region.

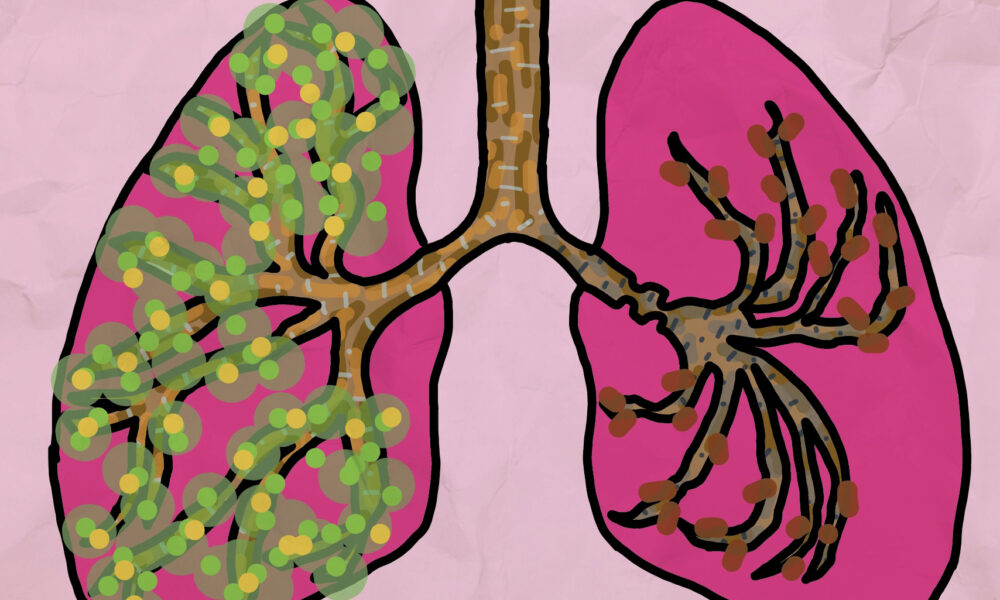

Although the study does not find a linear relationship between urban vegetation and childhood asthma development, it provides useful insights. For instance, asthma development in children was more frequent during the pollen, or “leaf-off” season—when deciduous trees shed their leaves, typically in autumn and winter. Conversely, during the “leaf-on” season, when deciduous trees develop a protective green canopy, usually in spring and summer, vegetation contributes to a reduced risk of childhood asthma.

“We know that exposure to air pollution is a trigger for asthma, and we have this idea that trees reduce that risk. But beyond having that idea, we don’t necessarily know the mechanism by which that may happen,” Kaiser said.

After acknowledging certain limitations in the study, such as the absence of both annual tree canopy (upper branches and leaves) measurements within the study range and potential risk factors at home, Kaiser clarified the research paper’s goal. He emphasized that the study did not intend to comprehensively explain how trees might alleviate, or aggravate, childhood asthma. Rather, it aimed to contribute valuable data to a growing understanding on the environmental context of health.

Medical practice represents a tangible example of how this expanding knowledge pool can be applied—a shift that, according to Kaiser, is still on the horizon.

“When you see somebody in a clinical setting, you should be asking about where they live and what they might be exposed to. In public health, we need to have an understanding of the context of health, beyond the health system and beyond individual risk factors,” Kaiser said. “In the last couple of decades, we’ve touched on that, but […] I would say the health system and education [are] still very far behind where they need to be.”

The study’s data not only illuminates the environmental context of health but can also guide action regarding urban greening. The decision to plant urban vegetation is straightforward since any additional green spaces are advantageous, whether for mitigating heat or generally enhancing respiratory health. Determining where to prioritize urban greening or what to plant, though, is a complex process requiring deeper understanding before any decision-making.

This study is not the first and likely not the last to contribute to the exploration of this topic. Nevertheless, Kaiser expressed optimism about the inclusion of environmental health in urban planning and health policy.

“If we take health as a global outcome, that allows us to integrate a lot of stuff that may seem kind of different, otherwise. It’s a nice way to present a more unified picture,” Kaiser noted.