Just about everybody loves seeing a good movie. Though a person’s experience is tied to many different factors, it generally boils down to whether or not the viewer can relate to what they’re seeing on screen and how fully they become immersed in this imaginary world. This is contingent on factors that the average audience member can easily identify: Acting, plot, and visual effects. But the connection also depends on a network of things that happen on-screen but largely go unnoticed—this known as the cinematography.

Cinematography comprises nearly everything about the visual ‘feel’ of a movie that is not explicitly part of the story, from the size of the screen, to the lighting, to what is and isn’t in focus on camera. Every light placement, every colour filter used, every lens chosen is the result of a series of active decisions made by the director and the cinematographer (usually listed as the director of photography in the credits). The goal of their work is to use their tools in a way that best compliments the movie.

Film 101

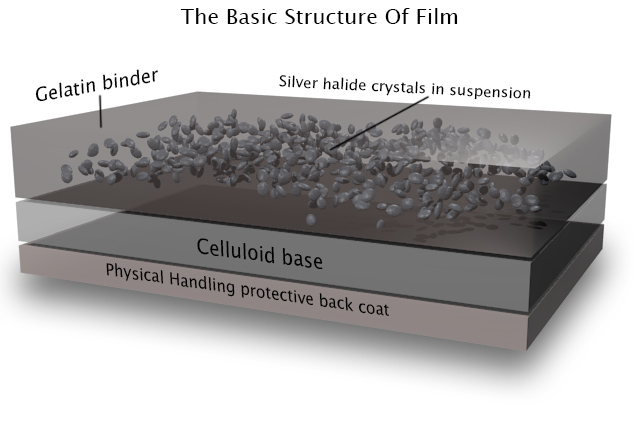

Film stock is the medium that, until the early 21st century, was the only way for movies to be recorded and shown to an audience. Film stock is a layer of thin plastic known as celluloid and is coated on one side with a gelatin solution. Suspended in that solution are tiny crystals of silver halide—light-sensitive particles—that capture an imprint of an image after the light that passes through a camera lens hits it. The film is then treated with a developing solution that reduces the silver halide to elemental metal, and the images captured on the camera become visible to the naked eye.

The number of silver halide layers applied and how the film is developed both play a role in the film’s final look. Standard black-and-white film uses only one halide layer (called an emulsion layer) while colour film requires three layers (cyan, yellow, and magenta). The chemical composition of those layers can differ widely between different brands of film in terms of the distribution of halide particles (this is responsible for how grainy the film looks), the stock’s sensitivity to light, and the proportions of chemicals used in each layer, resulting in the over-or under-saturation of certain colours. These differences can be be further influenced by how the film is actually developed. Exposure time, the developing solution used, and the temperature of the developing chemicals are all tools the cinematographer can use to give the film the look that best complements the movie it is a part of. For instance, to fully convey the bleak intensity of the storming of Normandy beach in Saving Private Ryan (1998), Cinematographer Janusz Kaminski intentionally skipped a step in the developing process so that the silver halide outweighed the colour emulsion, giving the film a greyer, less colourful tone.

Film stock

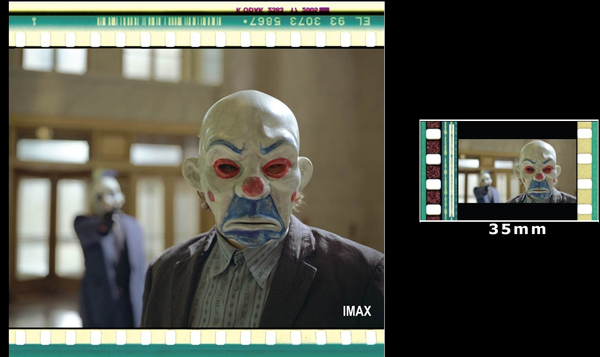

The width of the film stock is also important to how a film looks onscreen. Many studio films like Citizen Kane (1941), Vertigo (1958), and Pulp Fiction (1994) were shot using 35mm film stock, meaning the width of a frame of film was 35 millimeters in diameter. This was used because it had a high enough resolution—the wider the film stock, the higher the resolution—to be shown on a theatre screen. Lower grades of film, 8mm and 16mm, were used for home movies and educational films, respectively. On the other end of the spectrum is 70mm, the widest and most cinematic format.

Used mainly in IMAX films today, 70mm was once synonymous with what now considered blockbusters. Expensive films like Ben-Hur (1959), Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) were shot on 70mm film to give them a feeling of broadened scope and epicness. Since the amount of physical space that the camera can capture is doubled from that of standard film, filmmakers can convey the grandiosity of a crowd scene or the desolation of the vast Sinai desert in a way that 35mm can’t. Due to its high cost, 70mm film went out of fashion even before traditional 35mm film followed suit.

Digital vs. Analog

The combination of the high cost of film stock and the increased resolution that digital photography is capable of exhibiting have made traditional methods of film all but obsolete. In many ways, this is a good thing: Since spooling film requires a certain amount of bulk, and therefore makes the camera harder to move, the presence of digital cameras has allowed filmmaking to become more dynamic in its movement.

The decreased cost of filming with a digital camera combined with the low price of high-quality cameras has greatly democratized cinema, allowing anybody with a modest budget to create a professional-looking film. For instance, Tangerine, a 2015 critical favourite, was shot entirely on an iPhone but looks as sharp as any studio film released last year. The digitization of cinema has also allowed for the preservation and restoration of old film—film stock, which can be captured by a computer and digitally restored, usually through a process of painstakingly digitally removing imperfections caused by the degradation of time.

Despite the benefits of digital, a few purist directors like Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Martin Scorsese have been very vocal about their preference of traditional film, with Tarantino going as far as calling digital “the death of cinema.” They believe that “something special” is lost with the transition, and they may have a point. There’s an inexplicable warmth to the graininess of old films in the same way vinyl records have a certain feeling that digital music doesn’t.

Films like Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight are designed to make the audience more aware of cinematographic effects. But the truth is that very few people actually notice the difference between digital and film. So as long as cinema continues to reinvent itself, maybe it's okay that these techniques continue to change.