Next time you think you’re deciding between a salad and fries, your brain may have already subconsciously made the decision for you. A research team from the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital of McGill University and the McGill University Health Centre has shown that food choices are largely governed by past experiences.

“In our study, we were interested in learning about how people make decisions in regards to food,” explained Deborah Tang, lead author of the study. “We took 29 people and put them in an MRI scanner. We showed them pictures of food and asked how much they’d be willing to pay for each picture.”

This method, known as the Becker-DeGroot-Marshak auction, has participants bidding between $0 and $5 in $0.50 increments for each item. The best strategy is to bid what one is willing to pay for the item, which then enables the research team to determine how much a person is willing to pay.

The team concluded that the participants’ choices and willingness to pay were based on the caloric density—the amount of calories per gram—of the food. Iwnitially, the team believed that the participants would choose the healthier food items that were lower in calories; however, they quickly realized that this wasn’t the case.

It doesn’t matter how many calories a person believes is in the food, explained Tang.

“The brain creates this response to food based on previous exposure to it in terms of calories.”

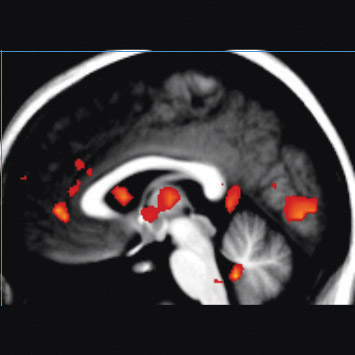

The participant will want to go for the food item that in the past has provided them with the largest amount of calories. These feeding patterns are signalled by an area of the brain known as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). The vmPFC reacts to stimuli and is responsible for decision-making. Brain scans of the participants from Tang’s study showed high activity in these regions during their bidding session.

The study also had participants accurately try to estimate the caloric contents of the food items they were bidding on. Surprisingly, the participants did a poor job determining the calories present in the foods; however, they still consistently chose the higher calorie option. This indicates that despite not being able to identify the higher calorie food, people will still choose it.

“While this is showing that subconsciously you don’t have a lot of control on this, [maybe] certain drugs can alter your brains response to food,” Tang said.

According to the latest Canada census, one in four people are obese and the ability to cut back on food by managing cravings could mean great things for those trying to lose weight. These urges involves another aspect that the team is investigating: The hunger hormone ghrelin.

“[Ghrelin] goes up before feeding, and down after,” explained Tang. “High levels of ghrelin leads you to eat more.”

Understanding the signaling pathways responsible for hunger urges can provide help to those suffering from type II diabetes and cardiovascular problems.

So, don’t feel bad the next time you’re reaching for the brownie you shouldn’t be having—your brain’s already decided for you.