In late June 2023, the Montreal sky turned orange-grey, the skyline overtaken by a thick haze. The city’s annual air quality report for that year showed that pollution reached its highest point in eight years and on June 25 and 26 of 2023, Montreal had the worst air quality in the world. The culprit? Wildfires.

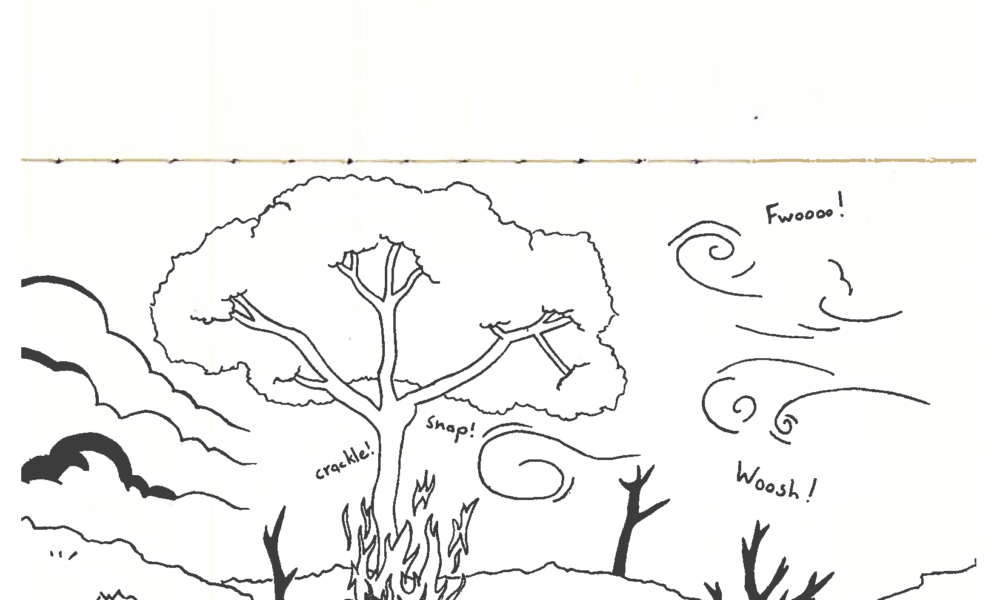

The 2023 Canadian wildfire season was the worst on record, scorching over 15 million hectares of land. While wildfires are a natural phenomenon, droves of research have connected continued climate change and global warming to longer and more destructive wildfire seasons. These fires may not be ablaze in or even near Montreal, but the summer of 2023 acutely showed how the infernos, carried in by wind, make their mark on cities.

But once wildfire smoke floats into a city, how does it disperse? How can researchers accurately model these patterns? Quinn Dyer-Hawes, third-year PhD candidate at McGill’s Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, set out to answer these questions in a recently published paper in the journal Building and Environment.

Wildfire smoke is made up of gases like carbon monoxide and methane, but also contains clouds of particulate matter. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5)—classified as having a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometres—makes up roughly 90 per cent of the total particle mass in wildfire smoke. Exposure to PM2.5 is one of the main health risks associated with wildfire smoke, with the Government of Canada reporting that there is no known safe level of exposure to it. Because of its abundance and relatively stable behaviour in the atmosphere, PM2.5 became the primary pollutant of interest for Dyer-Hawes.

His study used computational fluid dynamics—a way of modelling the movement of gases or liquids that can continuously flow (scientists group both liquids and gases as ‘fluids’). Such fluids, including air, can then be modelled using the Navier-Stokes equations. As Dyer-Hawes explained, however, these equations are extremely complicated and require a lot of computational energy.

“We use computers to be able to simplify those equations and then solve them because you are looking at very large scale areas. And if you were to do that all by hand, it’d take forever,” Dyer-Hawes explained in an interview with The Tribune.

These equations allowed him to track the movement of wildfire smoke by simulating wind, which, presumably, carries the pollution throughout the city. Dyer-Hawes found that the concentration of PM2.5 predicted by the model varied considerably across the city.

“There are areas in the city which have higher wind speeds and […] lower urban density, and these areas have better ventilation, and so they’re more easily able to carry the wildfire smoke out of them,” Dyer-Hawes said. “Conversely, there are areas where you have low wind speeds and very dense buildings, and these are areas where you can actually have buildup of wildfire smoke.”

This buildup of PM2.5 can have adverse effects on city dwellers, especially when the heightened particulate matter concentrations are compounded by other pollutants like car exhaust. According to Dyer-Hawes’ paper, being in poorly ventilated areas when PM2.5 concentrations are high could have hazardous health effects, although more research needs to be done to fully understand the impact.

“With climate change, we’re going to see more frequent wildfires, and so you can expect more cases where cities are being affected by wildfire smoke. So I think it’s something very important to pay attention to,” Dyer-Hawes said. “[Summer 2023] was definitely a bit of a wake-up call.”

This study, however, was primarily meant to test and validate a model that Dyer-Hawes will use in his future research. Looking to the future, he is working on modelling greenhouse gas dispersal through wind. According to Dyer-Hawes, Montreal does not have a robust inventory of localized greenhouse gas emissions. With his upcoming research, he hopes to get a better understanding of where they are coming from and if there are any significant sources that have been overlooked.