For some, the key to success on Valentine’s Day consists of an amalgamation of romantic gestures, boxes of chocolate, and dinner dates. However, no number of roses, Laura Secord truffles, or Chardonnay can amount to the necessary spark in our brains to fuel love.

While common notions of romance suggest that it is the heart that falls in love, many studies have found that love is a quantifiable process, in which the brain releases measurable euphoria-inducing chemicals.

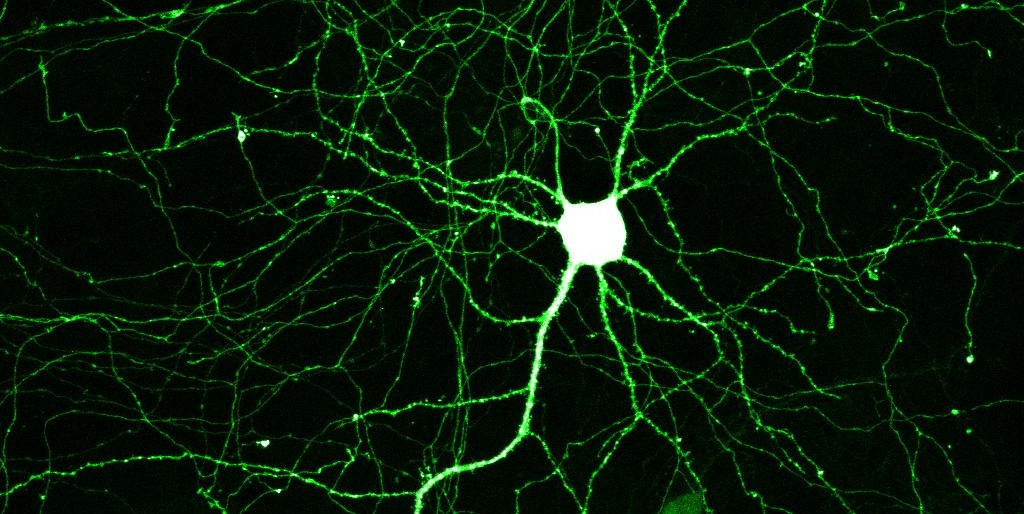

One such study, conducted by Syracuse University professor Stephanie Ortigue, suggests that love elicits a similar elated feeling to using cocaine. When a person falls in love, twelve different areas of the brain work together to release euphoria-inducing chemicals such as dopamine, oxytocin, and adrenaline.

Studies of the brain with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) also show why love causes such remarkable feelings. The earliest fMRIs of brains in love were taken in 2000. These revealed that the sensation of romance is processed in several areas, starting with the ventral tegmental—a clump of tissue in the brain’s lower regions. This region produces dopamine in the body, a chemical that regulates reward.

“This little factory near the base of the brain is sending dopamine to higher regions,” said anthropologist Helen Fisher in an interview with Time Magazine. “It creates craving, motivation, goal-oriented behavior, and ecstasy.”

However, if love can be broken down into a chemical phenomenon—butterflies in the stomach are actually the result of a chemical signal—it raises the question as to why certain individuals can elicit such a response from others.

Contrary to popular belief, love, according to our genes at least, is not a necessary aspect of life. Your principle job while alive is to conceive offspring, provide them with nurture, and then, obligingly, die so you don’t consume resources needed by the young. If our primary purpose is to breed, what drives humans to write poetry, buy flowers, and act impulsively in the name of love?

The answer lies in the fact that, while humans are designed to reproduce often, the survival of their offspring is also important. For this reason, as soon as humans reach adulthood, they begin to look for signs of good genes, and reproductive fitness in potential partners.

Smell is one of the most primal indicators that a potential partner is reproductively suitable. Humans, like all animals, have an intuitive understanding of whether a partner smells right. However, the distinction between someone who smells “good” or “bad” is less of a reflection of perfume, and more of an indication of good genes.

One set of genes that controls the adaptive immune system is known as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). In terms of genetics, it is more beneficial for people to have diversity in their MHC genes. In fact, conceiving a child with a partner whose MHC is too similar increases the risk of a miscarriage.

In a study conducted by the University of Bern in Switzerland, women were asked to smell different T-shirts worn by anonymous males, and then pick the ones that appealed to them. The results showed that women chose T-shirts worn by men with a genetically different MHC, suggesting that it is the desire for reproductive fitness that fosters attraction. If smell is not enough of an indicator, taste definitely is. Saliva also contains the MHC compound. According to associate professor of psychology at UCLA, Martie Haselton in an interview with Time Magazine, “kissing might be a taste test.”

It seems the hunt for reproductive fitness spurs the mating rituals attributed to falling in love. The elaborate practice of dating can be likened to a screening process—only once the right person has been found does the process pay off. At this point, the euphoria-inducing chemicals are released and love finally hits.