Rowan Stringer, a 17-year-old rugby player from Ottawa, suffered a concussion during a rugby match but ignored her symptoms and took to the field again less than a week later. In that second, and ultimately final, match on May 8, 2013, she suffered a second concussion that sent her into a coma—from which she would never wake up.

Stringer is far from the only athlete to have suffered a concussion practicing youth sport. Thirty-one per cent of Canadians who have participated in youth sports report having suffered at least one sport-related concussion, according to a 2015 study conducted by the Angus Reid Institute. While most concussion stories do not end as tragically as Rowan’s, they always threaten permanent damage to the brain. In turn, sports leagues for players of all ages have taken measures to curb the harm caused by concussions.

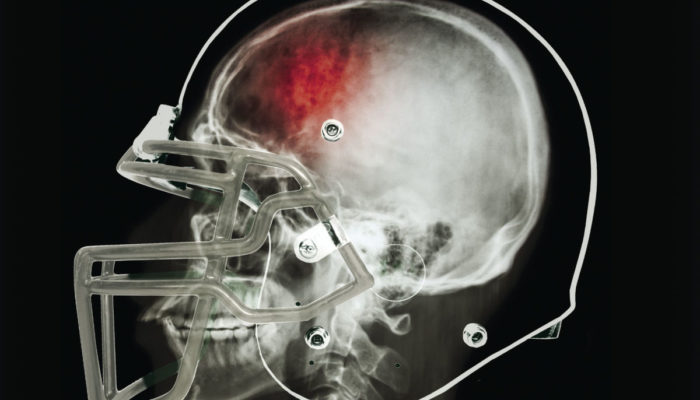

A concussion is a traumatic brain injury that occurs when a hard impact to the head or body jolts the brain, resulting in a temporary impairment of brain function. The brain is surrounded by three layers of membrane and cerebrospinal fluids that cushion it; however, upon forceful impact, these protective measures are not strong enough to hold the brain in place, allowing it to move within the skull. Such movement can affect the brain’s chemical equilibrium, damage nerve tissue, and cause bruising.

Typically, it takes one to two weeks to recover from a concussion, but optimal recovery times vary depending on factors such as age, mental conditions—including anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, or post-traumatic stress disorder—and the severity of the concussion. Rest is key to the healing process, but patients must often avoid bright lighting, screens, and strenuous brain activity, too.

Alyssa Crichton, BSc ‘18 and Martlet soccer player from 2013 to 2017, suffered a concussion after taking a couple of hard shots to the head in back-to-back games. After the second, she was removed from play and taken care of by a team of doctors and therapists, but her recovery was still long and painful.

“I had a headache every single day for about five months and was constantly in pain because of it,” Crichton wrote in a message to The McGill Tribune. “I couldn’t really do much of anything [….] I have had a lot of bad injuries in my life, but the concussion was a whole new experience.”

Professional sports are leading the way in concussion prevention policy, looking to medical professionals and research for guidance. Teams and leagues across North America have started incorporating protocols into their treatment practices, like the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT)—a standardized evaluation form to check athletes for concussions—return-to-play policies, and baseline neurological tests.

These are undoubtedly improvements compared to a decade ago, but professional sports still have a long way to go in addressing concussions. Concussions continue to slip through the cracks because of poorly-written protocols, inadequate implementation, and, in some cases, an appalling lack of policy. For example, the NHL places much of the discretion on teams to decide when a player should fall under concussion protocol. This procedure reduces the chance that the concussed player receives proper care because teams will always push for their players to return to competition as soon as possible. On the other hand, organizations like the MLB and NBA have implemented league-wide policies that strictly dictate when a player should be removed, how long they must sit out, and the conditions of their return.

Youth and collegiate sports leagues have followed their professional counterparts by writing concussion protocols into their own rulebooks. Most policies help responders decide when athletes should be removed from play and how long they should be kept out; however, especially in youth sports, these protocols are often unclear and are not consistently followed.

Dr. Taryn Taylor is the co-owner and medical director of the Carleton Sports Medicine Clinic and chair of the newly-formed U Sports Injury Surveillance Committee. Currently, each U Sports conference individually manages concussion protocols, but the committee is working toward implementing a nation-wide policy. She outlined some of their biggest challenges and priorities in designing new protocols.

“There is very little a physician can do once a concussion has occurred,” Taylor wrote in an email to the Tribune. “The best treatment is prevention. This can be achieved with encouraging fair play and respecting opponents, stronger penalties for unsafe play, rule changes, and skill development [….] Athlete and coach education is important to improve reporting of concussion symptoms to ensure athletes are removed from play if a concussion is suspected and to prevent athletes from playing with a head injury.”

Youth athletes don’t enjoy the luxuries of designated team doctors and trainers caring for their team, but there’s still plenty that can be done to protect them. Every state in the United States—and as of March 2018, Ontario, too—has passed concussion legislation specific to youth sports, detailing protocols on when an athlete should be removed and for how long, as well as requirements for educating parents and coaches on concussion identification and treatment. However, the gamechanger for youth sports will be to ensure that every athlete, coach, official, and parent is confident and consistent in taking a conservative approach when dealing with potential concussions during practice or a game.

“If [athletes] are being told that they are fine, or are being pushed into returning to play, they will convince themselves that they are okay and put themselves at risk of doing more damage,” Crichton wrote.

Because of that competitive inclination to keep playing, and because concussion symptoms lurk below the surface, progress for a safer concussion culture has been slow.

In January 2018, Dr. Scott Delaney, an associate professor in McGill’s Department of Emergency Medicine and team doctor for McGill Athletics, the Montreal Alouettes, and the Montreal Impact, published a study about why professional football players don’t come forward when they suspect they are concussed. The study concluded that players knew that if they did report a suspected concussion they would be removed from play, and that they did not always understand the danger of playing while concussed.

“I think it is still hard for a lot of people who have never had a concussion to fully understand the injury and how terrible it can be, because […] it’s an ‘invisible’ injury,” Crichton wrote. “If you can’t see it, it’s harder to believe that it’s actually there.”

Concussions will probably remain an inevitable part of athletics. Youth, collegiate, and professional sports leagues alike have been making a steady effort in the last 10 years to eliminate concussion-causing impact in sports—but it might be impossible to completely eliminate concussions.

That’s not the present goal, though. Instead, the current focus is on improving the attitudes of athletes and coaches toward concussions—from education, to diagnosis, to treatment.

“We have to somehow change the culture involved in concussions and make people better understand the risk and try to take the pressure off the players if they come forward,” Delaney wrote.

This goal is achievable and shows that the sports world is moving in the right direction. But the work doesn’t end with new legislation. Above all else, everyone in sports must understand and emphasize that, at least when it comes to concussions, health is always greater than glory.