CW: Mention of physical and sexual assault

On Sept. 2, Eliza Fletcher was abducted during her morning run in Memphis, Tennessee. Three days later, Fletcher’s body was found in a vacant lot roughly seven miles from where she was taken.

The tragedy of Fletcher’s death reaffirms the constant dangers of running while female-presenting. In 2016, Alexandra Nicolette Brueger was shot and killed on a run in rural Michigan. Three days later, Karina Vetrano was killed while on a run in New York City. Five days after that, runner Vanessa Marcotte was murdered in Princeton, Massachusetts. In 2018, Mollie Tibbetts, a University of Iowa student, and Wendy Martinez, a Washington D.C. resident, were both stabbed to death during runs. And in 2020, Sydney Sutherland was killed while running in Arkansas.

These stories are nothing new.

As a runner myself, I often run with a buddy, be it my dad or a friend. There are times, however, when I need to take time for myself—so I run alone, listen to music, and just think. But, running alone comes with the fear of being harassed or harmed.

Every runner has likely heard the tips: Don’t wear headphones, change your route, only run in broad daylight, and in well-populated areas. Even that, however, does not always suffice. Despite “doing everything right”, Wendy Martinez and Karina Vetrano were still brutally killed while simply going for a run in broad daylight in well-populated, “safe” areas. Regardless, the onus should not be put on the runner to avoid being harassed or murdered. Running should be a way to escape the stresses of everyday life, not an additional stressor.

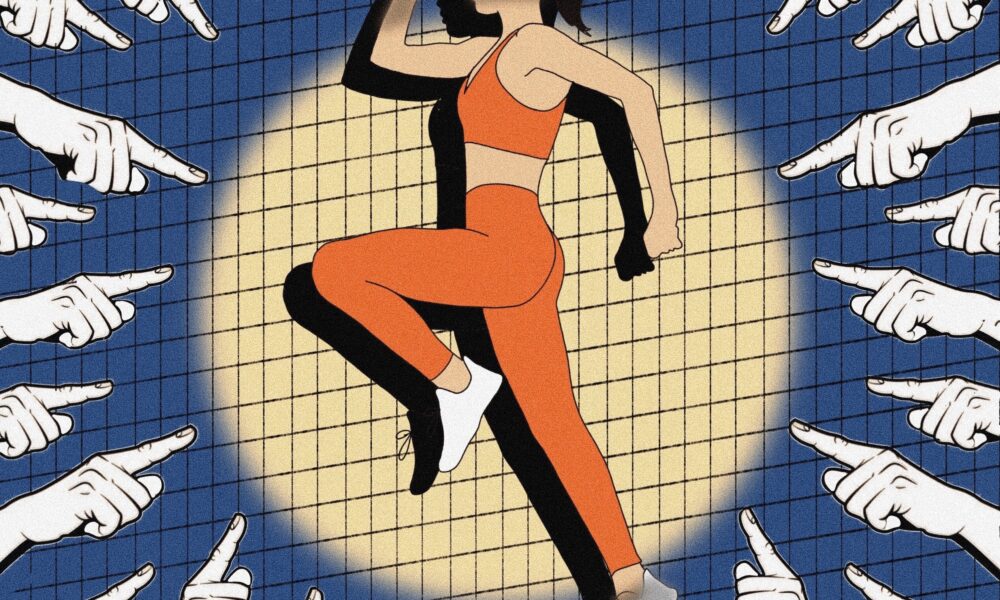

Verbal and physical harassment is far too common an occurrence for all women, runners especially. In a survey by Runner’s World, 60 per cent of female runners have dealt with harassment while on a run.

When I was in high school, I was running with my friends when a man drove by and rolled down his window to yell “Nice legs!”. I have also been honked at and stared at to the point of feeling incredibly uncomfortable.

Society’s acceptance of the hypersexualization and objectification of women enables predators to continually harass and attack women.

When a woman goes out for a run alone at 4:30 a.m. wearing a sports bra and shorts, as Eliza Fletcher did, she is not asking to be harassed or assaulted. A runner who becomes the victim of unwanted sexual attention is not to blame for harassment. And many women runners do not have the privilege of running during daylight hours, in safe neighbourhoods, with a buddy.

Instead of asking why she was running so early in the morning or what she was wearing, we should instead be asking why we, as a society, are okay with a culture of victim-blaming. Safety should not be conditional on what time it is, what someone is wearing, or what someone looks like.

Despite strides made towards ending the culture of sexual violence, known sexual abusers are still being elected into office and the gender pay gap still means that women are receiving $0.89 for every dollar a man makes doing the same work. Ending harassment for runners and other athletes means calling attention to how female-presenting individuals are treated as lesser beings or sexual objects, and actively working towards systemic change.

Being able to exercise in the way that most empowers you without fear of harassment or assault is a right everyone should have. Until running free of fear is an option for all people, we must hold each other accountable. Returning home from a run should be a given, not a hope.

Pingback: My body is not the enemy - The McGill Tribune