It’s no secret that Montreal is not a baseball city. The Expos moved out because nobody showed up to their games. Nobody came to watch Pedro Martinez throw fire every five days, or Tim Raines rob hit after hit on the outfield grass, or Gary “Kid” Carter fire bullets to second base. Some pointed fingers at Expos owner Jeffrey Loria, but in Montreal, baseball season had always been little more than a time to recover from the hangover of the Habs’ latest playoff run.

If you want to find a piece of baseball lore in Montreal, you would have to look in the right spot.

First, you’d have to go back in time to before the Expos brought Major League Baseball to Canada. Then you’d have to walk a bit—the opening of the metro is still 20 years away. Rush out of your 8:30 a.m. lecture (it’s a day game; there is no stadium lighting, not yet at least) up University and through the Plateau. A few blocks past Saint-Denis you would cut through Parc La Fontaine and hang a right.

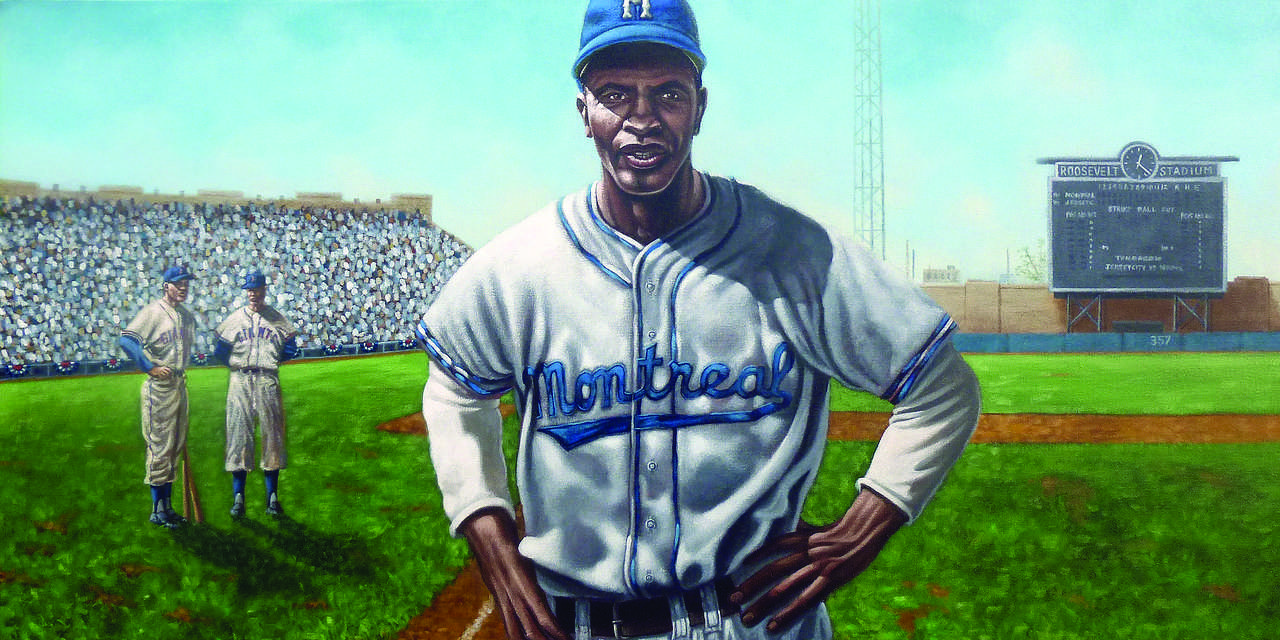

You have arrived at Delorimier Stadium. It’s Opening Day for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ top farm club, the Montreal Royals. The date is May 1, 1946. You take a seat and listen to the sound of 16,000 adoring fans screaming one man’s name: Jackie.

It was not by chance that Jackie Robinson, the man who broke the colour barrier in professional sports, came to Montreal to play ball. Despite having just fought a war in which the enemy was vilified for its horrific discriminatory practices, the United States remained thoroughly segregated. People may have been comfortable sending African-Americans overseas to die for their country, but they wouldn’t dream of letting a black player onto the hallowed fields of their national pastime.

As the story goes, the integration of African-American players into professional baseball was put to a vote in 1946. Of the sixteen major league owners polled, all but one voted against. The exception was Branch Rickey, president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

In Rickey’s eyes, the issue at hand wasn’t desegregation or civil rights. He saw a strategic advantage; dormant sluggers waiting to be handed bats and gloves. According to baseball historian Jack Jedwab, Rickey once confided that “the greatest untapped reservoir of raw material in the history of the game is the black race […] who will make us winners for years to come.”

As with all established traditions, segregation was not a status quo that could be slowly chipped away at. Rickey knew that he needed an athlete who could open America’s eyes so wide that they could never be fully shut again. He needed someone who could dazzle on the field and present an honest image off the field. In Rickey’s words: “We need to convince the world that I’m doing this because [he’s] a great ballplayer and a fine gentleman.”

After passing over established Negro League stars such as Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, Rickey found Robinson—an articulate, college-educated, soon-to-be-married Methodist—and the ‘Great Experiment’ was hatched.

Every detail was carefully planned out. Montreal was chosen due to its comparatively weak racial prejudices, and the fact that most of the Royals’ games would be played north of the Mason-Dixon line. The demarcation separated the Confederate states and the Union states during the Civil War and remained a cultural boundary in the years that followed.

The signing itself was kept a secret until October 23, 1945, months after Robinson’s arrival in Montreal. South of the border, the announcement stirred up a national debate, with baseball legends such as Roger Hornsby, Bob Feller, and Connie Mack vehemently opposed to the idea of possibly competing against a black player in the big leagues, let alone having one on their own team. Robinson, of course, was conveniently out of the American media’s reach, and as the cold winter months rolled by, the controversy was buried under metres of Montreal snow.

While popular retellings of the Robinson legend—such as Brian Helgeland’s recent Hollywood biopic 42—often gloss over this period, it can be argued that Robinson’s first winter in Montreal was the beginning of baseball’s desegregation. After experiencing rejection and hatred in countless American cities, Robinson was surprised when he was able to rent a room in the predominantly French-Canadian neighbourhood of Villeray without a problem. His wife Rachel, who spoke to the Montreal Gazette years later about her experiences, remembered the people of Montreal as warm and hospitable. The children of Avenue de Gaspé rushed to carry her groceries up the icy steps to the apartment, and neighbours began sewing maternity clothes when she became pregnant.

“It was likely that [Rickey] knew the Robinsons would be warmly greeted by the neighbours,” Jedwab said in a recent special to the Gazette

The division in Quebec has always been a linguistic one, and any racist undercurrents would have taken a backseat to the ingrained Anglo-Franco tensions.

“Since most people in the neighbourhood didn’t speak English, the couple was a kind of curiosity […] while the Robinsons were stared at on the streets, the stares were friendly,” Jedwab said. Although the family may not have been able to communicate with their neighbours save for hand gestures, they had found a place where “Jackie” would be recognized and respected first and foremost as a ballplayer, not a black player.

Unburdened by the weight of the civil rights narrative, Robinson took the International League by storm in 1946. The Royals began their season on a long road trip, but news of his prodigious exploits slowly filtered back to Montreal. Rumours swirled that he had knocked a three-run homer in his first at-bat and stolen home his next time on base.

By the time the Royals’ home opener rolled around, Montreal was in the grip of Canada’s first baseball frenzy. According to Toronto Star reporter Richard Griffin, Robinson was unable to join the team’s pre-game practice because he was too busy signing autographs for adoring Royals fans. The Royals won the game 12-9 and, nestled in the riotous crowd of 16,000; Habs legend Maurice Richard would remember the moment as the first time Montreal had cheered for something other than hockey. In a recent retrospective on the magical opening day, New York Times’ sportswriter Joe Sheehan wrote: “Robinson had fully justified [Rickey’s] precedent-setting break with what was described as a baseball tradition.”

Robinson would go on to lead his Royals to a 100-win season and their first Junior World Series title over Louisville. He led the league with a scorching .349 average to go along with 113 runs and 40 steals. After the final out of the championship game was recorded, fans poured out of the bleachers and rushed onto the field, chanting Robinson’s name. Sam Maltin, a stringer for the Pittsburgh Courier, famously described the scene at the time as “the only day in history that a black man ran from a white mob with love instead of lynching on the mind.”

But by no means was Robinson’s season with the Royals free of discrimination. The team would get off the bus in Florida or Georgia, only to find their games canceled because their second baseman was black. Griffin recalls that “On road trips […] no team hotel would take African-Americans.” Through it all, Robinson expressed no desire to retaliate nor turn back. He hoped that Americans listening to his games on the radio would slowly grow used to the idea of an African-American playing in the major leagues. Whatever abuse Robinson experienced on the road, he knew he could always heal his bruises back home. In their cozy apartment on de Gaspé, the Robinsons were accepted without prejudice.

While baseball tends to paint an overly-nostalgic image of history, one wonders if Montreal has been moving backwards ever since Jackie Robinson left town. All that remains of the hallowed grounds of Deloriomier on which Robinson played is a modest bronze plaque in honour of his accomplishments. Jarry Park Stadium, the Expos’ original field, has been repurposed as a tennis stadium; meanwhile Olympic Stadium, the most recent home of the Expos, stands as a shell of its former self.

The Expos have been gone for a decade now, and over the next few decades, their legacy will fade, as did that of the Royals. Soon, it may be hard to imagine that the crack of bat on ball ever sounded in this city. The role that Montreal played in the civil rights movement should not serve as a reason to put our city on a pedestal, but as a constant reminder of what Montreal once was, and what it can be.

Elie, I’m really glad you wrote about this important topic (and a personal hero of mine– Jackie)! I enjoyed reading your article, and am going to provide some resources that I think will help deepen and complicate your understanding of Jackie and race-relations in Montreal.

You write:

“The division in Quebec has always been a linguistic one, and any racist undercurrents would have taken a backseat to the ingrained Anglo-Franco tensions.”

Fortunately, there is a lot of scholarship dealing with the history of race-relations in Montreal before and after Jackie. I believe the most germane piece of evidence with respect to this topic is a Masters Thesis by Dorothy Williams entitled “The Jackie Robinson Myth: Social Mobility and Race in Montreal. 1920- 1960” availably online: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk2/ftp01/MQ39047.pdf . There you will get much more information about the context in which Jackie spent time in Montreal.

There are a few additional studies that will enhance your understanding of Montreal’s history of race-relations. I recommend:

Dorothy Williams, The Road to Now: A History of Blacks in Montreal

Charmaine A. Nelson (McGill Prof), Ebony Roots, Northern Soil:

Perspectives on Blackness in Canada

Dennis Forsyth (Prof at John Abbott College I believe), Let the Niggers burn: The Sir

George Williams affair and its Caribbean aftermath — this is about race relations in the late 60s Montreal and the infamous http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_George_Williams_Affair .

If you want a truly historical view of Jackie’s time in Montreal, you have to begin with the period of slavery in Quebec. I would look at:

Afua Cooper, The Hanging of Angelique: the untold story of Canadian slavery and the burning of Old Montreal

Robin W. Winks, The Blacks in Canada

Marcel Trudel, Canada’s Forgotten Slaves: Two Centuries of Bondage

That will provide an excellent overview and complicate the historic position of blacks in Montreal vs. the myth of racial tolerance in Canada. I hope you continue learning about Jackie and struggle between where he stands in our historical vs. mythical memory!