Golfer Lana Lawless is suing the Ladies’ Professional Golf Association and Long Drivers of America. Why? Because Lana, born a man, holds that the LPGA’s gender policy for entry, “female at birth,” is contrary to California state law. Lawless contends that by prohibiting her from competing, the LPGA is infringing the state’s civil rights law, as she is legally considered female.

In 2008, Lana won the Women’s World Long Drive Championships, organized and held by Long Drivers of America. This year, she’s not allowed to compete because the organization has changed its rules to mirror the LPGA’s. Lana wants the LPGA banned from holding competitions in California until the participatory requirements are changed. She isn’t the first transgender athlete to encounter obstacles. However, the LPGA is far behind most other sporting bodies in its policy.

Way back in 1976, transgender tennis player Renée Richards was denied entry into the U.S. Open unless she submitted herself to chromosomal testing. She fought the ruling by the United States Tennis Association, and in 1977, the New York Supreme Court supported her. Richards played professionally that year and by 1979 was the 20th ranked women’s singles player.

In 2003, the International Olympic Committee Medical Commission called a committee meeting “to discuss and issue recommendations on the participation of individuals who have undergone sex reassignment… in sport.” The “Stockholm Consensus” concluded that transsexuals had the right to compete in Olympic events if: (a) they had undergone sex reassignment surgery before puberty, and (b) post-puberty, that they had been legally recognized as of their assigned sex, had undergone hormonal therapy for a “sufficient length of time to minimise gender-related advantages in sports competitions,” and had undergone external genitalia changes and gonadectomy at least two years prior to the request for eligibility.

The IOC reserves the right to judge athletes on a case-by-case basis and to perform “sex-tests” on those athletes whose sex they find suspicious.

In the world of golf there’s already a precedent for Lawless’ current legal battle. In 2004, Australian golfer Mianne Bagger became the first transsexual woman to ever play in a professional golf tournament. Concurrent with her acceptance at the Australia Women’s Open, the Ladies’ Golf Union changed its policy to allow her to compete in the British Open. Not long after, the United States Golf Association changed its policy as well, opening the U.S. Women’s Open to transsexual women. Since then, Bagger has competed professionally in both Europe and Australia

Still, the LPGA has lagged far behind these other golf organizations and Lawless is attempting to force them to play catch-up quickly.

The issue of transgender athletes fighting to compete is one that will only grow in public consciousness as the issue bceomes more exposed. As more athletes come forward, outdated gender rules will be cast aside.

Nevertheless, the issue is not so cut-and-dry. Even transgender sports legend Renée Richards criticized Lawless’ efforts, saying that physically strong transgender women could have an advantage (Lawless once weighed 245 pounds), particularly in something like a sprint or a weightlifting event. However, she noted that since Lawless is 57 years old, there probably wouldn’t be too much harm in letting her compete, since she’s not going to be a threat to professionals on the tour.

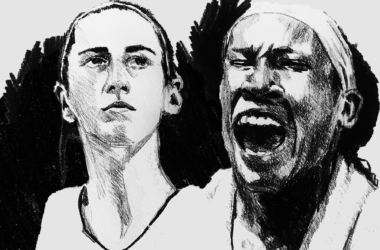

The question has to be asked though: Is that the right way to judge whether transgender women should be allowed to compete? Only allowing them in if they’re either too old or too bad to beat the “females at birth”? I don’t think so, but I don’t have an answer to what the acceptable parameters are. The only thing that is for sure is that this will be an issue of intense debate over the next 10 years and that the LPGA’s policy is going to come under a Caster Semenya-like level of scrutiny.