I am pulled to consciousness. My body is torn from the tender embrace of the hot oil from which I was imagined. I am a blank slate with neither thought nor feeling, but, soon, my purpose shall be revealed to me.

“Who am I?” I wonder as I am surrounded by hundreds of my compatriots. “What is my purpose?” I query as my brethren and me are carelessly thrown into a box and covered by some hastily-torn foil.

As a bemused club executive takes us toward a building I know to be called Leacock, I see my surroundings: a gaggle of Toronto girls talking about their recently-failed midterm. A second-year airpod-wearing poli sci bro, pontificating on the latest SSMU drama to a member of the AUS executive team. A lanky French boy in Adidas Stan Smiths is about to slip on another patch of—oh, there he goes.

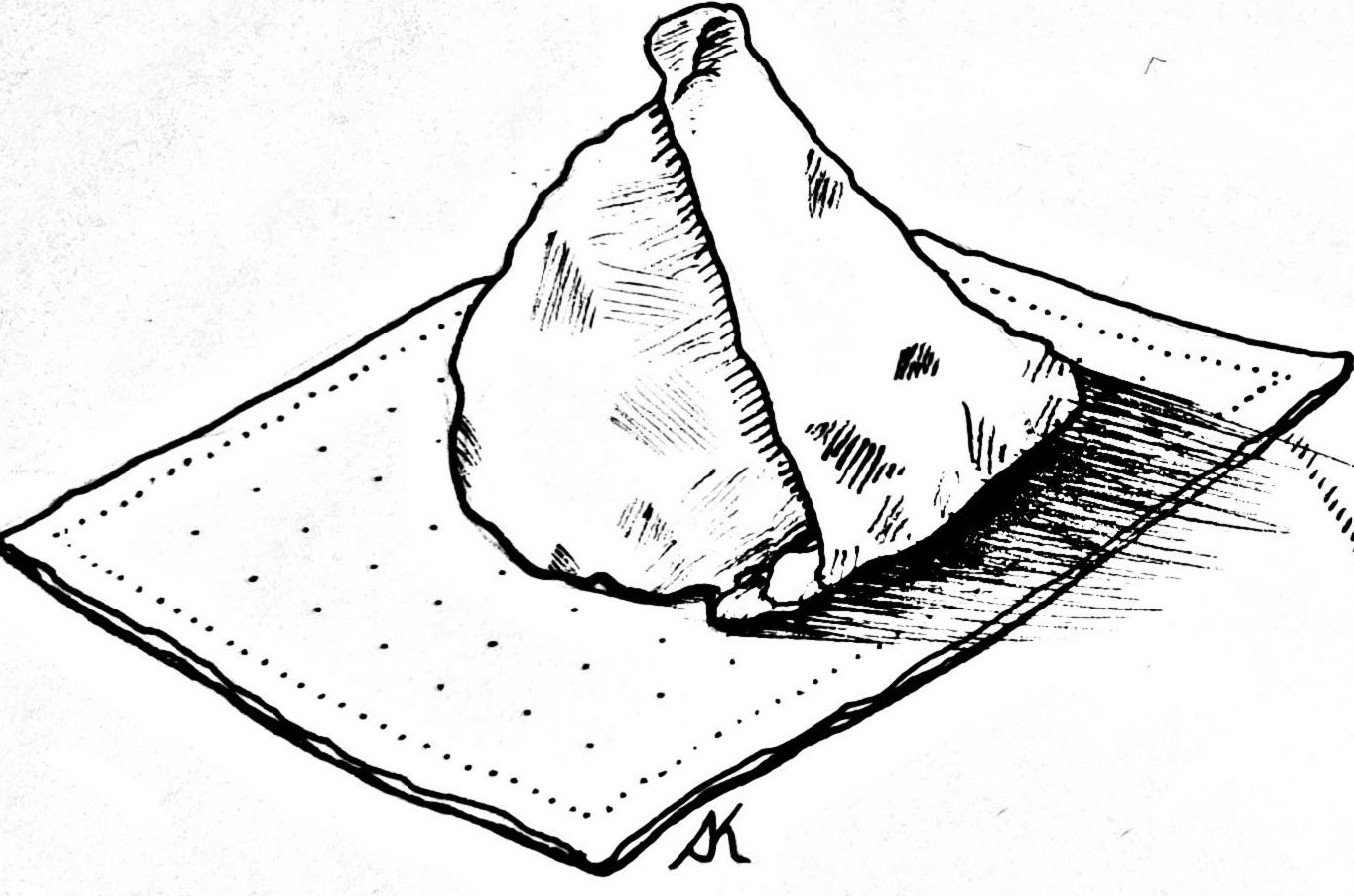

Our dwelling is slammed onto a rickety table, and, within seconds, exhausted students flood toward us, flinging toonies into a plastic container. Three-by-three, we are lifted out and wrapped up in a page of the Tribune News section that nobody will read because, let’s face it, everything is online these days. Why are they still printing these things?

My purpose, I now understand, is to fill the void left by poorly-scheduled midterms, overpriced Premiѐre Moisson coffee, and mercurial Montreal weather. Yet, this purpose of mine—a band-aid to cover a fundamentally-broken system—is growing old. All I can offer is a one-lunch stand, but these students deserve so much more; they deserve an emotionally nourishing, balanced diet.

There is a fundamental problem to my existence: Much like neoliberalism, I look a lot better on paper than I actually am. I’m speaking, of course, of the three-for-a-toonie ‘bargain,’ which appears economically superior, since one’s extra dollar buys 33 per cent more samosa than the one-for-one option. However, there are externalities which neither the student nor the laissez-faire paradigm take into account.

What I’m trying to say is this: The three-samosa deal includes one samosa too many. Thus, while the other two samosas are devoured with chutney and desperation within moments, I, the third samosa, am left to fend for myself. Although it is only half-past noon, I feel the sun setting on my existence. Soon, dusk becomes midnight as I am tossed into a garbage bin.

Ergo, my story closes. I lay here, sandwiched between two of those cakey Timbits that nobody ever wants to eat and a flyer for exam tutoring—which that student really should have kept because the midterm he is about to sit will take him for a ride. In my misery, I ponder the great theorists—Rousseau, Sartre, Nietzsche—and I come to a realization: There is no God, but there is the samosa creator. He lives within every meltdown, each failed exam, every lost love. He lurks behind every wall, in the asbestos in Schulich, under the counter in what was once Gerts. God is dead, but he survives. Nay, he is thriving.