Little Burgundy, also known as la Petite Bourgogne or St-Antoine, is a small neighbourhood of around 10,000 people in Montreal’s Sud-Ouest district.

Located around two kilometres southwest of McGill campus, Little Burgundy is only a 30-minute walk away. The area borders Shaughnessy Village and the 720 Highway to the north, Pointe-Saint-Charles and the Lachine Canal to the south, Griffintown and Guy Street to the west, and Saint-Henri and Atwater Street to the east. To reach Little Burgundy by public transit, take the metro to stations Georges-Vanier or Lionel-Groulx.

Architecturally, the district is similar to other mid-density neighbourhoods in the Sud-Ouest, with multiplexes, red-brick facades, and minimal setbacks from the street. Former industrial buildings, now converted to apartments and condos, dot the canal and its surrounding streets.

In the early 20th century, Little Burgundy became the centre of Montreal’s Anglophone Black community. Nearly 90 per cent of men in the neighbourhood were employed by the nearby Windsor and Bonaventure rail stations, despite many of them having college degrees, as few other industries were willing to employ Black workers due to pervasive anti-Black racism. During the sleeping car era, most hires were porters; many described it as demeaning work that fixed the image of Black workers to the railroads. The transport companies provided housing in Little Burgundy for the porters, and as the area became more inhabited, Black-run services and facilities that catered to these workers and their families became concentrated in the area. Other businesses typically refused services to Black customers.

In the 1920s, a decade now considered a golden period of Montreal’s Black history, there were numerous nightclubs and casinos that catered to white tourists looking to gamble and drink. Musical performances were a key part of the nightlife; Black musicians of the neighbourhood helped Montreal become one of the three main jazz hubs on the continent. Jazz clubs such as Rockhead’s Paradise hosted greats like Louis Armstrong, Nina Simone, and Sammy Davis Jr., while also serving as a launching pad for local talents like Oscar Peterson.

But when the Great Depression spread to Canada, Little Burgundy was hit particularly hard and the neighbourhood was unable to hold onto the success of the 1920s. To make matters worse, in the 1960s, mayor Jean Drapeau launched a series of urban renewal projects on the island of Montreal. The city’s intentions in Little Burgundy were two-fold: First, they wanted to “modernize” the area with a “slum clearance” project, and second, they wanted to build a highway to connect the majority-white suburbs to the downtown core.

The project was immense and irrevocable. The city sent in assessors to photograph the buildings and identify which ones would be expropriated, and pushed the project through without consulting local residents. Little Burgundy’s homes, restaurants, and business were all expropriated. The final result was a gentrified neighbourhood devoid of the culture and community it had built over the years. Many Black families were displaced: In 1966, the Black population was over 14,000, but by 1973, it had dropped to only 7,000.

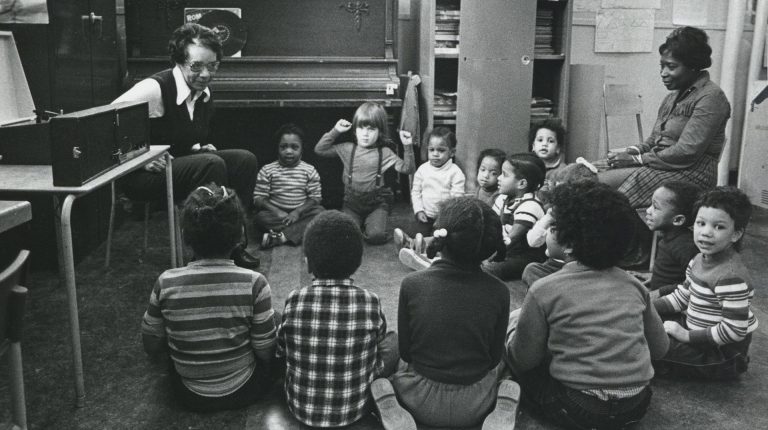

The expropriations of the ‘60s had lasting consequences,, including the dispossession of key institutions that served the Black community. The Negro Community Centre, for instance, was a community hive and safe space where neighbourhood members gathered and immersed in art and music, but it closed in 1989 due to financial struggles and was later demolished. Black Montrealers have called for its revival in recent years. The Black community in Little Burgundy is not as numerous as it had been before the urban renewal programs, but community activists have made local efforts to highlight its past by renaming the streets and parks and installing public art honouring community icons.

Today’s Little Burgundy is quite different from that of the 20th century. In recent decades, the borough has undergone even more gentrification, kickstarted by the creation of a linear park along the Lachine Canal, the revitalization of the Atwater Market, and the redevelopment of former industrial buildings. Members of Little Burgundy today continue to fight the dispossession of Little Burgundy’s working-class population and the neglect of its history—one that is central to the story of Montreal.