Beyond the obligatory appearances on TV, the witch is a pervasive figure, taking on different forms throughout history. Her classic imagery—black pointed hat, broomstick, old haggard face, and unsavory wart—is a staple of Halloween festivities. In contemporary popular culture, witches have appeared as archetypal fairytale villains, teenagers in coming of age stories, and even as violent matrons overseeing a dance school. As modern witchcraft is on the rise, she might even be a friend or classmate. To understand the witch’s complex evolution, however, we must return to her origins.

One of the first historical accounts of witches is in the biblical story “The Witch of Endor,” where a witch summons a dead prophet’s spirit to help King Saul achieve victory in battle. In ancient Greece and Rome, authorities of magic used sorcery to prevent unwanted storms, bring rain for agriculture, or increase wealth. Before the 14th century, witches were not seen as inherently demonic, but as merely possessing a special relationship with divine forces that allowed them to concoct spells and connect with the supernatural.

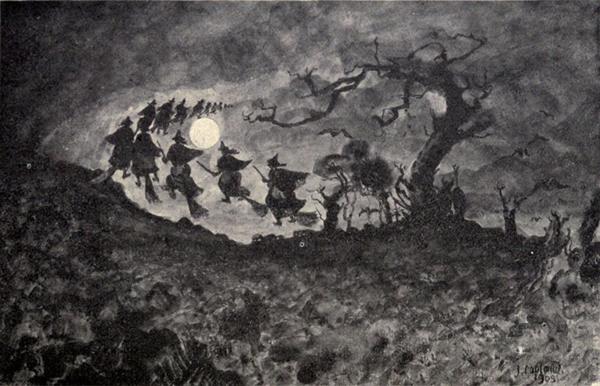

In the middle ages, however, the popular European perception of witchcraft was transformed into dangerous anti-religion, threatening patriarchal Christian societies and traditional female roles. Witches were believed to conspire on the Sabbath to have orgies, worship unholy images of various animals, and feast on the roasted flesh of unbaptized babies. Beliefs of women flying in the night, their minds held captive by the devil, instilled fear in medieval peoples. The stereotypical image of witches riding broomsticks reflects anxiety surrounding those trespassing the barriers of domesticity.

The witch craze was stimulated by the publication of Malleus Maleficarum in 1486, a guide that taught inquisitors and judges how to identify, interrogate, and condemn witches. The book asserted that an inherent lack of intelligence in women made them defenseless against the devil’s seduction. Apart from the Bible, the book sold more copies in Europe than any other continent until 1678.

Since the beginnings of English literature, writers have been fascinated by the character of the witch. Tropes of devilish, mysterious women trace back to antiquity, such as in the tale of Hecate, the Greek goddess associated with magic, witchcraft, the moon, and necromancy. In Macbeth, a trio of devilish witches deliver dual prophecies that incite the play’s conflict, while in Morgan le Fay, Geoffrey Monmouth’s witch is portrayed as a healer, seductress, and royal enemy.

Despite her various forms and shapes, the witch epitomizes female independence, yielding insuppressible power, her madness never submitting to those who fear it. The witch is a powerful icon of rebellion and autonomy—not only women, but also people of colour and individuals in the queer community have turned to modern witchcraft, disempowered and frustrated by dominating systems of governance.

“Being of mixed heritage, I find myself trying to incorporate elements from my various ethnic and cultural backgrounds,” Devon Ellis-Durity B.A. ‘20 (Concordia University) wrote in a message to The McGill Tribune. “What got me interested in witchcraft was the ability to work with the elements and further my connection with nature. Witchcraft has allowed me to further align with my morals.”

Modern witchcraft is multifaceted, its inherent openness welcoming to everyone regardless of background. Ultimately, being a witch in the 21st century is to engage in a hallowed practice that connects the individual with the earth and their community.

“When I first started learning about witchcraft, it was introduced to me as something which has no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way, that everyone practices, values, and relates to it differently,” Mitzi Ellemers, U2 Arts, wrote in a message to the Tribune. “It is very forgiving in this sense. Personally, my relation to witchcraft is about solidarity, oneness, and reverence for the earth and all natural elements and a sisterhood with the people who I practice with.”

I agree. I remember when I first started practicing,it was a time when It felt lije i had no control over anything .it gave me a sense of belonging and self worth. I am grateful for being able to return to a more natural feeling of self awareness along with my own sense of worth.