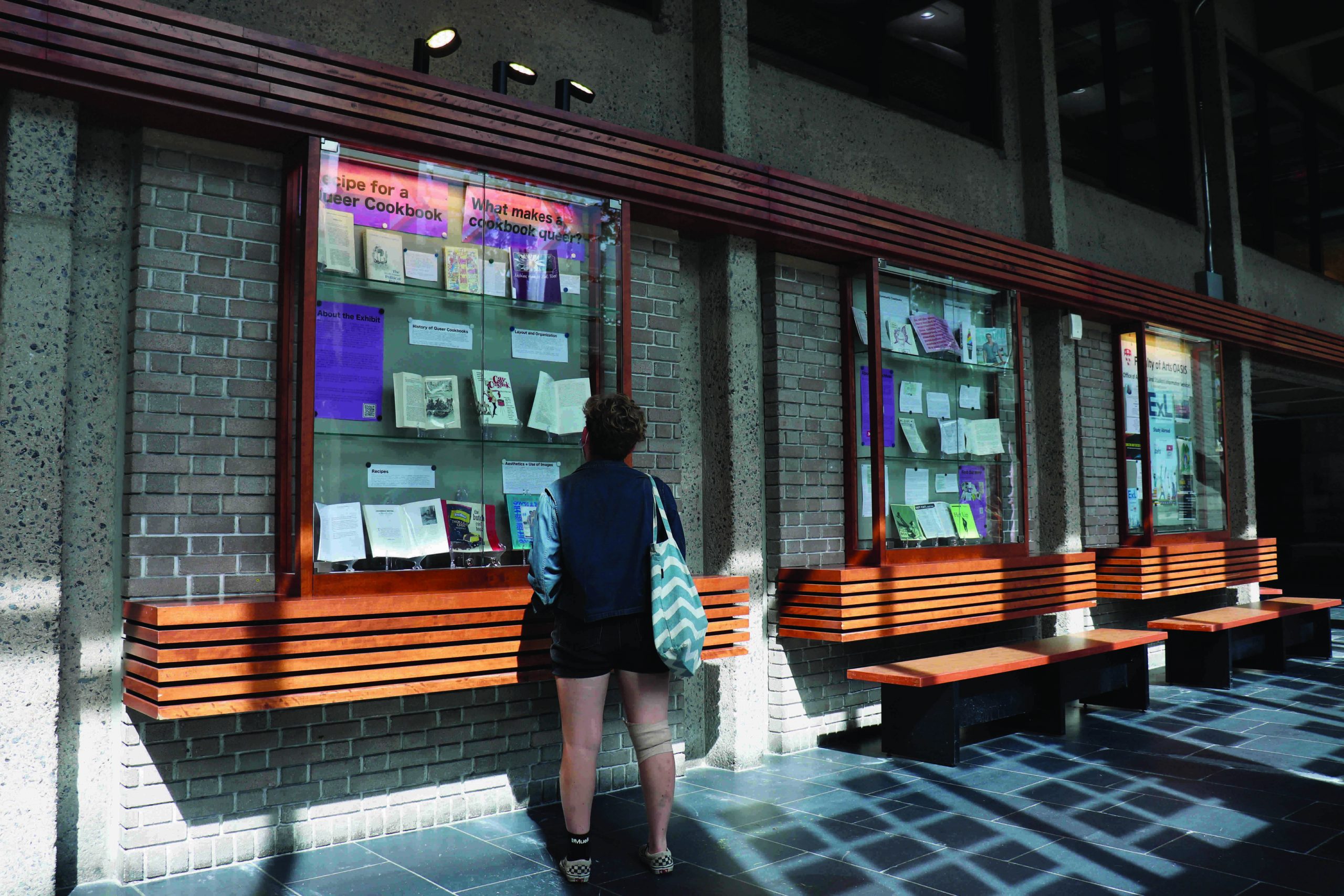

Up until Dec. 20, students walking down the Leacock corridor will notice a new addition to the glass cases lining the wall: The “A Recipe for a Queer Cookbook” exhibition.

Curated by Alexandra Ketchum, a faculty lecturer at McGill’s Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies, the exhibit showcases more than 20 cookbooks that, for one reason or another, can be described as queer.

Ketchum’s interest in queer cookbooks stems from her research into feminist restaurants. Her love for the subject was born out of a formative experience from her undergraduate years, when she visited Bloodroot, a self-proclaimed feminist restaurant and bookstore located in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Ketchum ended up writing about the spot in her undergraduate honours thesis and eventually pursued her master’s and PhD at McGill, where she studied feminist restaurants, cafes, and coffee houses in North America.

The exhibit itself is inspired by lesbian feminist restaurant owners, some of whom put together their own cookbooks.

“Bloodroot [has produced several cookbooks],” Ketchum said. “The first one was in 1980, called The Political Palate. In many ways, it’s like a political manifesto and a cookbook.”

While she has many research interests, Ketchum explained that amidst the difficulty of the pandemic, putting together the project was an opportunity to have fun with her research.

“I’m into these cookbooks as artifacts and what they tell us about history, what they tell us about different cultural movements,” Ketchum said. “It allows me to ask […] deep questions about identity, queerness, politics, access to publishing and so forth, but it was also just fun.”

When asked what exactly makes a cookbook queer, Ketchum pointed to the importance of the viewer’s own interpretation.

“Part of the exhibit was to […] invite viewers and readers […] to think about, ‘what do I think makes it queer?’” Ketchum said.

However, there are some characteristics Ketchum includes in her own personal definition of a queer cookbook. For example, the authors of the book must, in some way, identify as part of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, and the cookbook should connect to queer communities—be it through fundraising efforts, raising awareness about queer issues, or gathering recipes from community members.

But overall, the cookbooks vary––some are plant-based, some have religious affiliations, and some emphasize sexuality and include nudity. A few of Ketchum’s personal favourites include The Kitchen Fairy’s Be Gay! Eat Gay!: The Gay of Cooking and Lagusta Yearwood’s Sweet and Salty.

While most of the cookbooks on display come from her own personal collection, Ketchum also collaborated with the Quebec Gay Archives and Quebec Lesbian Archives, who provided the zines. Beyond loaning material for the exhibit, Ketchum wanted to collaborate with the archives in order to inform viewers that they are available for research on queer history

“[Viewers or readers] can scan the QR codes [in the exhibit] and find out how to make an appointment where they can see what other collections are available, or what’s digitized,” Ketchum said. “And all of a sudden, archives don’t feel like these spaces that are behind locked doors that you can never go to.”

For those who are not able to visit the physical exhibit in Leacock, the digitized version is available online at The Historical Cooking Project, a blog Ketchum has been editing since 2013.