Loneliness is hard to define because it is premised on a feeling of lack—a lack of contact, of laughter, of connection, of empathy, of dependence. It is a lack that weighs heavy at 8 p.m. on McGill campus as students slowly make their way home—their stomachs growling and vision blurry from hours spent reading under the library’s halogen lighting. It is a lack found in the way students quietly file out of the library at night with their headphones on, passing each other.

It is the noiseless way that any student filing out of the library feels compelled to reach into their pocket for their phone and call someone—anyone. As they consider calling a parent, they stop themselves short. They don’t really have anything specific to say, they just need to connect with someone. But they worry that if they call just to chat, their parents will assume they’re feeling ‘lonely.’ Slowly they slip the phone back into their pocket, and walk home in silence. This is loneliness.

“Loneliness is so much more than the absence of people,” Eve Kraicer, U3 English, said. “It’s having an actual impulse to articulate how you are doing, with nowhere to go and no one to listen.”

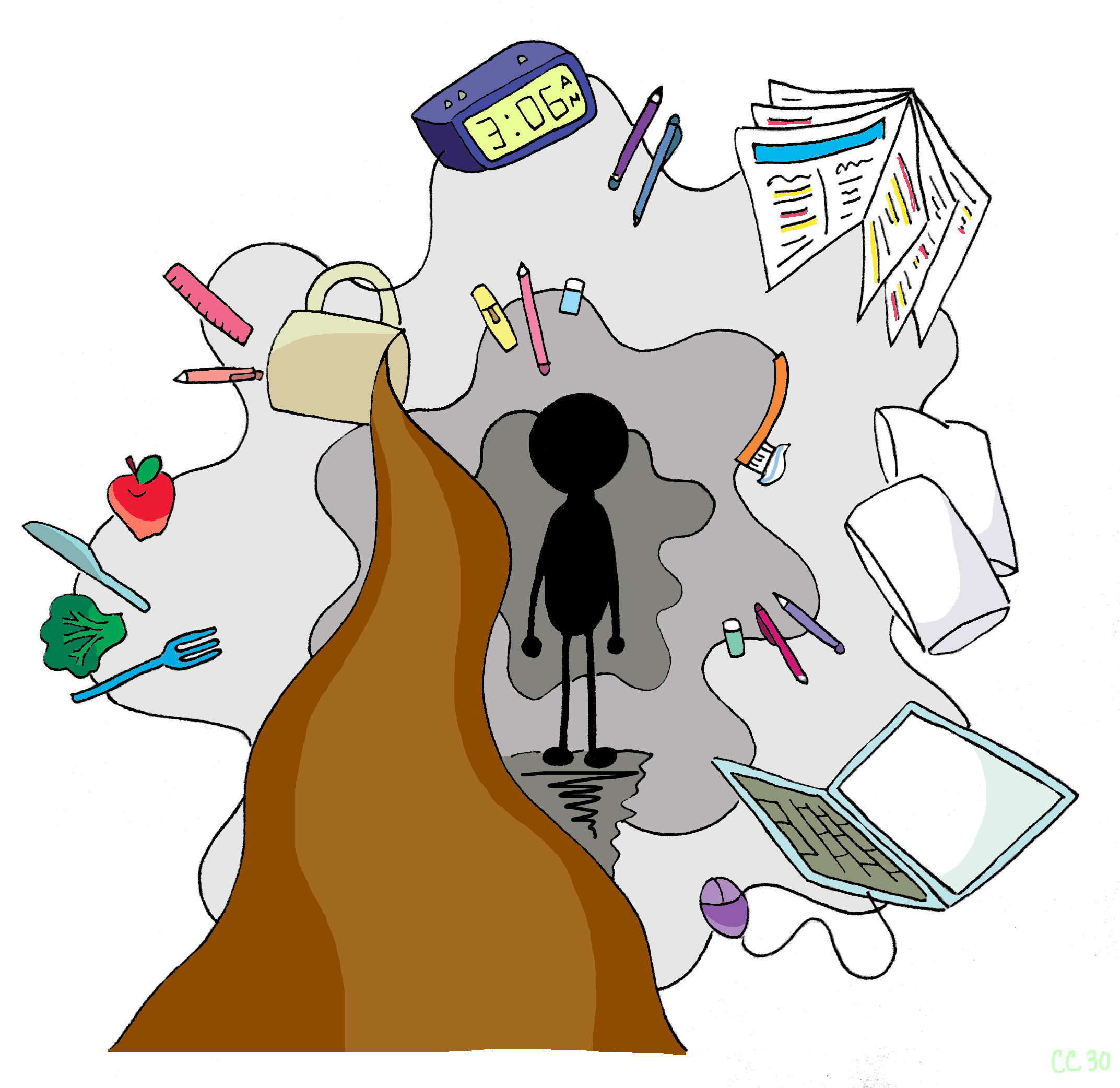

Students are often left without people to listen to them because loneliness is ingrained in the university experience. At age 18, most Canadian students transition from high school to university, and suddenly their old web of community-building tools—teacher-organized clubs, required courses, strict meal times, and a structured 8:30-3:30 schedule—disappears. For the most part, McGill students choose their own classes, consulting academic supervisors and health services is optional, and, after first year, students are responsible for determining their own food and housing. For some, this responsibility is rewarding, but for others it can make university an exceptionally lonely space.

In a recent viral article in The Guardian, titled “Neoliberalism is creating loneliness. That’s what’s wrenching society apart,” journalist and psychologist George Monbiot suggests that the brutal competition and pressure students are put under in the education systems of industrialized countries is creating lonely people.

“Human beings, the ultrasocial mammals, whose brains are wired to respond to other people, are being peeled apart. Economic and technological change play a major role, but so does ideology,” Monbiot writes. “Though our wellbeing is inextricably linked to the lives of others, everywhere we are told that we will prosper through competitive self-interest and extreme individualism.”

Neoliberal societies, as Monbiot explains, are those that see competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. At McGill, this extreme individualism—which prioritizes the success of the individual above the community and fosters extreme loneliness—is ingrained into the culture of the university. Entry-level class sizes can enroll up to 1,000 people, and students often feel pressured to study before socializing in order to keep up with their classmates. McGill’s academically rigorous setting pits students against each other and the bell curve.

“Usually my friends spend approximately the same amount of time studying as I do, so I don’t need to choose between studying and socializing” Gabrielle Trzcinski, U4 Engineering, said. “However, during busy weeks I sometimes need to prioritize studying over socializing, which can make me feel left out or lonely, and can also add to the stress of trying to get things done on time.”

The competitive nature of university is built into the institution’s landscape. Students are quick to point out the lack of community spaces on campus and common rooms in residences. For example, a singular common room is made for 200 students to socialize in each of the upper residences, and doors that close and lock automatically in La Citadelle and New Residence Hall. The spaces first years are welcomed into in the first week of September are, at the level of their construction, far from welcoming. This trend continues beyond first year institutions. Many buildings on campus, including the SSMU, are not conducive to social interaction.

“I think the institution, just from its very architecture, creates loneliness,” Noah Witte-Winnett, U4 Arts, said. “Literally, the spaces that exist within the university for people to get together are terrible, like the Madeleine Parent room has heaters that can be so loud you won’t hear what people are saying. The SSMU building in general—there is a whole fourth floor I didn’t know about, with clubs up there.”

Although students try their best to counteract the austere geography of campus—there are incredibly well trained floor fellows in each residence, and the active presence of social groups and initiatives like intramural sports teams, Midnight Kitchen, and SSMU minicourses—it is difficult to counteract the institutionalized forms of loneliness at university. For Ines Dubois, U3 Arts, first-year residences are a clear example of this.

“The residences do a good job at fostering communities, but their prices are inconvenient,” Dubois said. “Only people that can afford over $1,000 per month get to make friends, and that’s not right.”

Dubois draws attention to the fact that at McGill, the lack of community spaces on campus turns connection into an experience that is inaccessible to students without the financial means. Currently, for students who live at home or in independent off-campus housing, loneliness is a very real concern.

Even for those students who can afford the rez experience, the loneliness that is ingrained in McGill’s landscape creates a marginalizing process of maturation that often lets students fall through the cracks. However, the reality is that student life at McGill is not very different from how the real world functions, and independence can also yield unexpected gifts.

“The older you get [as an individual], the fewer institutions there are that try and help you,” Kraicer reflected. “I think that the experience of growing up is one of learning how to understand and navigate loneliness.”

Like many people, Kraicer says she has experienced her fair share of isolation. In fact, moments of aloneness seem to have become a given in our university setting. Yet, Kraicer is hopeful that there is something to be gained by being exposed to loneliness. She points to the fact that university provides students with a wealth of opportunity to forge meaningful relationships outside the institution.

“The optimistic part of me hopes that the connections that you make that you have to work at, the ones you make when you’re older […] are more meaningful than the ones you make when you’re in elementary school,” Kraicer said. “I hope that the farther I get from being told how to do this, the more I’ll be able to do this for myself, and I’ll know how to do it in an individual way that works for the communities I want to build, and the communities I need.”

Solitude or time enjoyed by oneself should not be equated with loneliness, per se. However, there are preventative measures students can take when alone time begins to turn into feelings of disconnection. Whether it’s making recurring dinner plans with roommates or family, scheduling regular mental health check-ups, or simply asking friends how they’re doing and really listening to their response, Kraicer notes that the only way to combat loneliness is through active connection. In this way, a period of loneliness can be a formative experience. Although individualism and competitiveness are intrinsic to the university campus, the students that populate it are also intrinsically social beings. The conflict this creates is at the root of loneliness, but it can also provide the fertile ground in which meaningful communities flourish.